...click here to read the previous part

AGRICULTURE

Agriculture, Forestry and Land Use: 18.4% Agriculture, Forestry and Land Use directly accounts for 18.4% of greenhouse gas emissions. The food system as a whole – including refrigeration, food processing, packaging, and transport – accounts for around one-quarter of greenhouse gas emissions.

A 2021 UN report called for reform of the world’s $540bn in farming subsidies to help the climate and promote better nutrition. Livestock and food production are among the biggest emitters of carbon but also enjoy the most state support, the report says.

As much as 17 per cent of all food produced is lost or wasted. Converting land for agricultural use has led to a 70 per cent reduction in global biodiversity alone, and half of all tree cover, according to the UN report. Food production, is also a big polluter of air, freshwater and oceans. The UN estimated that such hidden costs to public health and the environment totalled about $12tn a year. That included $6.6tn in health problems caused by obesity, undernutrition and pollution; $3.3tn from agriculture’s effects on the climate and the environment; and $2.1tn due to wasted food and fertiliser leakage.

As a result, the real cost of food and its production was “undervalued”, the UN said, and there were better ways for governments to support food production such as that in India’s Andhra Pradesh, where conversion to 100 per cent chemical-free agriculture led to more stable yields and fewer crop losses.

“Repurposing agricultural support to shift our agri-food systems in a greener, more sustainable direction — including by rewarding good practices such as sustainable farming and climate-smart approaches — can improve both productivity and environmental outcomes,” said UN Development Programme administrator Achim Steiner.

“Governments have an opportunity now to transform agriculture into a major driver of human wellbeing, and into a solution for the imminent threats of climate change, nature loss and pollution,” said Inger Andersen, executive director of UN Environment Programme.”

Both Steiner and Anderson are right. However, farming subsidies — which include tariffs, price support and aid for inputs such as fertilisers — skewed production towards those sectors that were also among the biggest carbon emitters, the report said. The situation is particularly acute in richer countries that consume proportionately more dairy and meat. This reflects the power and influence of the agricultural lobbies and the agribusiness that now dominate the sector. This has to be confronted if the sector is to make a contribution to saving the environment.

Concentration of Power in the Agricultural Business

Six corporations—Monsanto, DuPont, Dow, Syngenta, Bayer and BASF—control 75 percent of the world pesticides market.

Only four corporations—ADM, Bunge, Cargill and Dreyfus—control more than 75 percent of the global grain trade.

In the USA 80% of beef packing and 70% of pork packing are controlled by 4 multinationals.

The size and influence of these mega-companies enables them to largely dictate what America’s 2 million farmers grow and how much they are paid, as well as what consumers eat and how much groceries cost.

The economic power of the corporations has contributed to their growing political power which in turn has led to laws that put profits before food and worker safety, consumer rights and sustainability.

During the 2020 election cycle, the food industry spent $175m on political contributions, compared to $29million in 1992. Two-thirds of the contributions went to Republicans.

Those who harvest, pack and sell food have the least power: at least half of the 10 lowest-paid jobs in the USA are in the food industry. Farms and meat processing plants are among the most dangerous and exploitative workplaces in the country.

“The meatpacking industry is much more dangerous now than in the 1990s, and the biggest factors are consolidation and cutting corners of worker safety,” said Debbie Berkowitz, director of the worker health and safety program at the National Employment Law Project.

In Europe the situation for workers in the meat industry is no better. A recent investigation uncovered that Meat companies across Europe have been hiring thousands of workers through subcontractors, agencies and bogus co-operatives on inferior pay and conditions.

Europe’s £190bn industry has become a global hotspot for outsourced labour, with a floating cohort of workers, many of whom are migrants, with some earning 40% to 50% less than directly employed staff in the same factories.

About 1 million people work in Europe’s meat sector, with unions estimating that thousands of workers in some countries are precariously employed through subcontractors and agencies.

“The system is sick everywhere across Europe. It’s based on cheap prices for meat, on the exploitation of labour,” said Enrico Somaglia, deputy secretary general of the European Federation of Food, Agriculture and Tourism Trade Unions. “You have workers elbow to elbow doing the same work, but under different conditions.”

Enrico is right, it’s all about producing cheap meat to keep competitive edge and to achieve market share in the growing markets of the developing world.

Despite the fact that numerous scientific reports have found that rich countries need huge reductions in meat and dairy consumption to tackle the climate emergency,

between 2015 and 2020, global meat and dairy companies received more than US$478bn in backing from 2,500 investment firms, banks, and pension funds, most of them based in North America or Europe, according to the Meat Atlas, compiled by Friends of the Earth and the European political foundation, and Heinrich Böll Stiftung.

With that level of financial support, the report estimates that meat production could increase by a further 40m tonnes by 2029, to hit 366m tonnes of meat a year.

Although the vast majority of growth in demand was likely to take place in the global south, the biggest producers will continue to be China, Brazil, the USA and the members of the European Union. By 2029 these countries may still produce 60% of worldwide meat output.

Across the world, the report says, three-quarters of all agricultural land is used to raise animals or the crops to feed them. “In Brazil alone, 175m hectares is dedicated to raising cattle,” an area of land that is about equal to the “entire agricultural area of the European Union”.

“The burning of the Amazon and the darkening of skies from Sao Paulo, Brazil, to Santa Cruz, Bolivia, have captured the world’s conscience. Much of the blame for the fires has rightly fallen on Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro for directly encouraging the burning of forests and the seizure of Indigenous Peoples’ lands.

“But the incentive for the destruction comes from large-scale international meat and soy animal feed companies like JBS and Cargill, and the global brands like Stop & Shop, Costco, McDonald’s, Walmart/Asda, and Sysco that buy from them and sell to the public. It is these companies that are creating the international demand that finances the fires and deforestation.

The transnational nature of their impact can be seen in the current crisis. Their destruction is not confined to Brazil. Just over the border, in the Bolivian Amazon, 2.5 million acres have burned, largely to clear land for new cattle and soy animal feed plantations, in just a few weeks. Paraguay is experiencing similar devastation.”

From a report in 2019 that rightly focuses on the big agricultural players behind Bolsonaro’s burning of the Amazon. Bolsonaro is a greedy and dangerous man, but he’s just a symptom rather than the cause, along with the range of politicians across the globe happy to look away from the damage caused by excessively powerful global agribusiness.

The Desertification of Spain

“Desertification is one of the world’s big four environmental areas of concern, together with climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution,” says Elias Symeonakis, an expert on the subject at Manchester Metropolitan University. “We depend on those areas that are degrading . . . for our food and our population. Once they are degraded, there is not much you can do.”

In Spain, about 20 per cent of land is already desertified, largely for historic reasons such as the destructive mining and over farming that followed the change of use of land expropriated from the Catholic church in the 18th and 19th centuries. In such areas, productive land has become incapable of yielding substantial crops for human or animal life, although some vegetation may hang on. Satellite imagery shows that a further 1 per cent of Spanish territory is actively degrading because of intensive agricultural practices, although a greater area is indirectly affected, too. “It is like a black hole,” said Gabriel del Barrio, a researcher at the state-run Arid Zone Experimental Station in Almería, one of the most affected areas. “This 1 per cent endangers the countryside for kilometres around it . . . using up water and causing other damage.”

Del Barrio, like many other experts, links desertification to altered land use, the industrialisation of agriculture and intensive irrigation. Such changes have helped increase Spain’s income from agriculture by almost 50 per cent in the decade to 2020. But agri-industry also uses almost seven times as much water as all Spanish homes.

Modelling by Jaime Martínez Valderrama at Alicante university indicates that the soil for wheat and sunflower crops in Córdoba province could be exhausted in six decades. The olive industry is another example, while the crop traditionally requires little to no irrigation, it is now often grown in high-density orchards where the plants resemble bushes rather than trees that can be machine-harvested, a big advance in productivity from the age-old tradition of farmworkers beating trees until the olives rain down. But such intensive farming also has greater water needs. In the provinces of Jaén and Granada, the olive industry is the main water user. In Andalucía, agriculture is responsible for almost 80 per cent of the region’s total water consumption.

Experts worry that current trends are unsustainable. “It’s an old saying: ‘The more water, the sweeter the fruit’,” said Vicente Andreu Pérez, a senior researcher on desertification at Spain’s National Research Council. “But we can’t increase agricultural profits indefinitely. Everything has a limit and if we arrive at the limit in this case we won’t be able to go back.”

Drinking Water Resources Destroyed

In Lastras de Cuellar in the central Castilla y Leon region, nitrates and arsenic have made the water undrinkable for the village's residents, who number 350 in winter and nearly 1,000 in summer.

And across the country, dozens of villages are suffering the same fate because groundwater resources are at risk from agricultural pollution, a lack of water quality controls and drought.

Every Monday, the villagers walk to the main square in Lastras to buy multipacks of mineral water in 1.5 litre bottles, sold at a discounted price, which some take away in wheelbarrows. (More about plastic water bottles later)

In Castilla y Leon alone, 63 municipalities were without running water in March, according to the region's main television station.

Nitrate levels are a cause for concern, with nearly 28 percent of Spain's groundwater monitoring stations registering a concentration close to or above the potability threshold.

Fully 22 percent of Spain's overall surface area -- which covers 506,000 square kilometres (195,000 square miles) -- is exposed to nitrate pollution due to the nature of the soil or through agricultural activities, the environment ministry says.

Individuals can make a difference by eating locally and eating less meat. However, this monumentally fails to address the crucial problems that lies in the power and reach of global agribusiness and the hold it exerts over political leaders, a power and influence that allows it to pursue environmentally damaging practices while receiving state subsidies that augment that damage, from governments that proclaim their Green commitment,

The drive for more profit and yield from the land irrespective of the consequences is killing the planet. At national and international level, there will be no escape from the environmental emergency unless this political and economic battle is fought and won and agriculture is profoundly transformed in the interests of all people, particularly in the developing world.

FASHION

The industry contributes between 3%-10% of Greenhouse Gas emissions according to various definitions. The consensus seems to be at the higher end. The World Bank uses this figure and is very critical of the industry in this 2019 report with good reason.

This is an important industry. It is valued at some $2.4 billion globally and directly employees 75 million people throughout its value chain. It is the world’s third-largest manufacturing sector after the automobile and technology industries.

Fast fashion is the real enemy, the fashion industry’s operating model is exacerbating the problem by stepping up the pace of design and production. Collection launches are no longer seasonal; the replacement of clothing inventories has become much more frequent.

Many low-cost clothing stores offer new designs every week. In 2000, 50 billion new garments were made; nearly 20 years later, that figure has doubled, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. The pace of apparel manufacturing has also accelerated consumption: the average person today buys 60 % more clothing than in 2000, the data show. And not only do they buy more, they also discard more as a result.

Less than 1 % of used clothing is recycled into new garments. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation estimates that every year some USD 500 billion in value is lost due to clothing that is barely worn, not donated, recycled, or ends up in a landfill. 40% of clothing purchased in some countries is never used.

It can be cheaper for internet retailers and fashion brands to dump or burn returned goods, rather than attempting to find another home for them. This not only means the greenhouse gas emissions produced in manufacturing the clothing are wasted, but further emissions are released as it rots or burns. The US Environmental Protection Agency estimates that in 2017 10.2m tonnes of textiles ended up in landfills while another 2.9m tonnes were incinerated. In the UK an estimated 350,000 tonnes of clothes end up in landfill every year.

By the year 2030, the fashion industry is predicted to increase its water consumption by 50 percent, and its carbon footprint will increase to 2,790 million tons while fashion waste is predicted to hit 148 million tons, according to the Copenhagen Fashion Summit.

In addition to all the above, the fashion industry is a great user of sweatshop labour in developing countries.

This is a classic capitalist industry of excess in that it produces a lot of stuff that nobody really needs in order to satisfy a set of manufactured and imposed wants and desires in order to make a lot of money for the few people at the top. Aja Barber, author of Consumed: The need for collective change; colonialism, climate change & consumerism, says that a change in the culture in and around the industry is necessary:

“We need more people not selling things online. We need them giving information and encouraging people to re-wear their clothing. We need more people shouting against the message. We have to overpower that message and [over-consumption] has to stop being cool,” she says.

Sustainability campaigns and shopping features may lead people to believe that buying differently is the answer – an organic cotton T-shirt rather than a new one, a pair of recycled polyester cycling shorts rather than from virgin polyester – but, as Barber notes, “if you’re over-consuming, even if it’s sustainable garments, it’s still over-consumption”.

The issue is that modern brands flourish on over-production and over-consumption. Weekly, even daily, stock drops keep customers buying at a lightning-fast pace. The average consumer bought 60 per cent more clothing in 2014 than they did in 2000 but kept each garment for half as long. Given that, in the seven years since 2014, the likes of Boohoo, Shein, and Pretty Little Thing have boomed, that figure may well have trended upwards.

Technological advances may make some production processes less toxic for the environment but this is an industry that will always encourage people to buy more and buy more often. Production levels will need to significantly reduce if the industry is to become less destructive and fashion companies will need to either educe their income expectations or pursue alternative revenue streams But the issue, Barber explains, is that “very few well-established brands are willing to do that”. Nor will that option prove attractive to their investors and bankers.

If we are serious about improving the environment this is an industry that needs to be seriously controlled and its basic instincts impaired. Serious tax penalties for dumping clothes and for environmental damage through supply chains should be considered.This is an industry that prospers through creating artificial needs and making people buy more, it’s part of the DNA, advertising and the use of “influencer” platforms should be seriously restricted. We should also look at utilising the resources of the industry to produce clothing at a reasonable need for the people who need it most e.g. people in developing countries, old people in the winter, rather than a series of vanity purchases by the wealthy.

FOOD RETAIL

In the wealthy world we are wasting several tonnes of food every day. For example, in the UK, people waste as much as 1.9 million tonnes of food yearly.

As part of a general rationalisation of agriculture we need to restrict the ability of supermarkets to offer “2-4-1” deals and other marketing devices that encourage over-consumption and waste; these measures should be coupled with taxes on sugar and other incentives to reduce the consumption of that product. Apart from the health benefits, the production of sugar is a highly water intensive operation, especially from sugar cane which has deep roots.

The increase in global demand for sugar is resulting in high water consumption, air and water pollution, soil degradation, and change in natural habitat. It is estimated that 10% of soil is lost during harvest of beet sugar and 3-5% of soil in sugar cane harvest. This has resulted in the clearing of natural habitats such as rain forests, coastal wetlands, and savannah.

This will directly impact the interests of food retailers, most of whom are big sugar pushers, but is one more instance of the interests of the planet not coinciding with those of global capitalism.

Packaging, Plastic and Bottled Water

Food retailers waste lots of packaging per day across the world. This increases plastic pollution, one of the leading causes of thousands of marine mammals' deaths. Cows, whale, dolphin, and porpoise species are some animals that consume plastics and die after a short while.

The industry should give priority to researching alternative means of packaging but its highly unlikely that a sector so focused on improving its own margins and exploiting its purchasing power to squeeze those further down its supply chain will dedicate the necessary resources to that project. A change in philosophy and practice is required. Nowhere more so than in the production and sale of plastic water bottles, available in every large retail outlet and an environmental disaster.

Producing plastic water bottles affects the conservation of non-renewable resources. About 99% of plastics originate from oil, natural gas, and coal, all unrenewable. If no changes are made, the plastic industry will account for 20% of global oil consumption by 2050.

Manufacturers use over 17 million barrels of oil to meet America’s annual demand for bottled water.

A large amount of oil needed to manufacture single-use plastics like water bottles is wasteful and not at all economically efficient. Bottled water companies are virtually pouring limited resources down the drain. The European plastic water bottle industry alone consumes 4%-6% of its oil and gas resources.

Furthermore, the energy required to produce plastic bottled water is 5.6-10.2 MJ per litre. It is quite a bit higher than tap water, which requires about 0.005 MJ of energy. Also, a lot of energy and water resources go into manufacturing a bottle of water. About 6 litres of water is needed to produce 1.2 litres of bottled water.

Across a large part of the planet tap water is perfectly safe and bottled water is not hugely healthy or beneficial in comparison. But this remains an enormous industry due to capitalism’s marketing prowess at creating needs, every retail store has a large stock of bottled water.

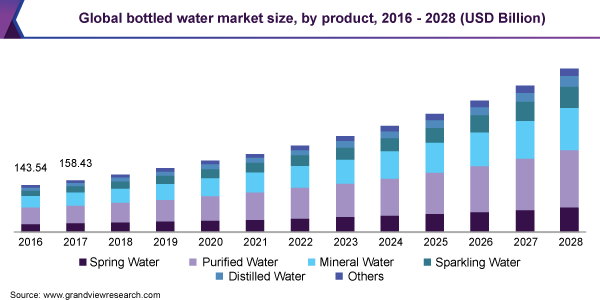

“The global bottled water market size was valued at USD 217.66 billion in 2020 and is expected to expand at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.1% from 2021 to 2028. Portability, easy usage and installation process, and minimal maintenance costs are the key factors to drive the market over the next few years. Furthermore, rising consumer consciousness towards the health benefits of consuming bottled water is projected to drive market growth over the forecast period. Inclination towards bottled water rather than ordinary water, particularly among younger consumers, drives product sales.

Observing this trend, several restaurants are providing bottled water to meet consumer demand. Water seems to have hit a sweet spot with health-conscious buyers. The rapid expansion of restaurants in the U.S. is also foreseen to create a significant demand for bottled water in the upcoming years.”

From , And look at the projected growth in this toxic industry,this report

The production and retail of bottled water needs to be taxed or seriously restricted. The sale of re-useable water bottles should be subsidised/promoted and the benefits of tap water, maybe combined with water filters, should be advertised.

About 8 million tons of plastic enter the oceans every year and kill more than 1.1 million seabirds and animals annually.

As these plastics degrade, they break down into microplastics that produce carcinogenic toxins that endanger marine life. Plastic accounts for 80% of the world's marine debris. If we do nothing, there could be more plastic than fish in the oceans by 2050.

Prominent players in the global bottled water market include:

We have to be prepared to take on these big names and their political influence if the necessary change is to come to this sector.

STEEL

The iron and steel industry is responsible for 11% of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and will need to change rapidly to align with the world's climate goals.

As a key input for engineering and construction, it is the world’s most commonly used metal, providing the foundations of the modern industrial economy. Since a method for inexpensively mass producing the iron alloy was developed by English inventor Henry Bessemer in the 1850s, a sprawling industry has grown which today turns over $2.5tn and employs millions of people.

To meet global climate and energy goals, steel industry emissions must fall by at least half by the middle of the century, according to the International Energy Agency, with declines to zero pursued thereafter.

Steel’s carbon intensity comes down to the principal route for extracting iron from its ore. Towering blast furnaces heated to above 1,000C are loaded with iron, lime and coke, a fuel derived from metallurgical coal that removes the oxygen molecules from iron oxide. A by-product of this chemical reaction is CO2. A significant amount of energy is required to heat the iron ore, to melt it and to actually separate the oxygen from the iron in the iron oxide molecule, the lowest-cost energy carrier is carbon-based. That combined with its high-temperature properties is what makes coke so important to iron and steelmaking and it’s really hard to replace. While environmental policymakers dream of a “circular economy” where resource extraction and waste is minimised, recycling by itself cannot provide the answer for steel, which is already the most reused material on earth.

“If we really want to contribute to realising the climate goals set in the Paris agreement, then there’s a quite widespread consensus that only doing further efficiency improvements in the blast furnace will not be enough. Breakthrough technologies are needed urgently” says Martin Pei, chief technical officer at SSAB, a Swedish company at the forefront of these efforts.

ArcelorMittal, Europe’s biggest steelmaker, has estimated that decarbonising its facilities on the continent in line with the EU’s drive to eliminate net greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 will cost between €15bn and €40bn. “These technologies will increase the cost of our steel. It is not cheap, and our customers should be ready to pay,” says executive chairman Lakshmi Mittal.

Herein lies a problem, how will this impact competitiveness and returns in an industry that is already beset by overcapacity and profit volatility? China accounts for 50% of the world steel market and generates about 2 tonnes of CO2 for each tonne of steel it produces compared to one tonne. China has said it will aim for carbon neutrality in steel production by 2060. 39 years is a long time in the current climate change emergency and the competitive pressures in this industry may well prevent all players from making the kind of changes that the planet needs in Steel production combined with the sheer technical difficulties in effecting those changes.

The Swedish group, SSAB, which is seeking to remove fossil fuels from every stage of the steelmaking process, has estimated that metal from its experimental hydrogen-based route (replacing iron ore) will initially be at least 20 to 30 per cent more expensive. “We believe H2 is most likely to be the solution to get to zero emissions. The key issue is cost,” says Goldman Sachs’ Della Vigna, who reckons that it will become economically viable at a carbon price of around $220 a tonne. Yet for mills to switch en masse to clean hydrogen, there would need to be a massive expansion in renewable energy infrastructure. Germany, for instance, would require additional renewable power equating to about 20 per cent of its current electricity consumption to convert its steel sector to DRI based on green hydrogen, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency.

This demonstrates how only so much scope for change is within the steel industry’s own control, significant levels of planning and coordination are required along, with international cooperation regarding the curtailment of competitive imperatives, the willingness of investors to tolerate lower profitability and customers to accept higher prices.

All this takes us back to two factors mentioned earlier in this paper:

the need for integrated planning, recognising interdependencies, with clear objectives driving the right behaviours to extricate ourselves from the climate emergency;

given the difficulties and extended timeframes of producing “Green Steel,” we need to think about producing and consuming less.

“We need transformational change operating on processes and behaviours at all levels: individual, communities, business, institutions and governments. We must redefine our way of life and consumption.” As per the leaked Part II of the IPCC report

Box “Carbon Taxing: Not Enough”

Carbon taxes currently only cover around a fifth of global emissions, just 4 per cent are covered by a carbon tax of at least $40 a tonne — the minimum rate that might be compatible with the goal of keeping the rise in global temperatures well below 2 degrees. In fact, a tax rate of €120 a tonne would be “more in line with recent estimates of overall social carbon costs”, according to the OECD.

“Carbon pricing as it stands isn’t climate action; it’s just virtue-signalling. Any government trying to get more ambitious hits resistance. The uprising of France’s gilets jaunes in 2018 sank Emmanuel Macron’s attempt to hike fuel prices by a few cents per litre.”

Simon Kuper in the FT: https://www.ft.com/content/90d786b6-c8b0-4ae2-9556-697672648778

Apart from the political realities of imposing serious carbon tax prices that may leave many poorer members of society much worse off, carbon taxes underestimate the extent to which we are facing a fundamental system problem rather than some market failures.

According to Daniel Rosenbloom, Jochen Markard, Frank W. Geels, and Lea Fuenfschilling of PNAS:

“The necessary transitions entail profound and interdependent adjustments in sociotechnical systems that cannot be reduced to a single driver, such as shifts in relative market prices. In mobility, for example, a low-carbon transition might encompass interacting developments around new vehicle technologies (e.g., autonomous electric cars), infrastructures (e.g., vehicle charging stations and high-speed rail), business models (e.g., mobility as a service and intermodal transport), and regulation (e.g., emission performance standards) but also changes in city planning (e.g., reduced urban sprawl) and lifestyles (e.g., telework and local vacations). The market failure framing fails to appreciate the broad scope of the climate challenge and the sweep of system elements that must undergo change. And so, the resulting solution orientation is far from sufficient.”

By increasing the relative price of carbon-intensive goods and services, carbon taxing is designed to incentivize the adoption of existing low-carbon technologies and stimulate the development of low-carbon innovations. Investments in low-carbon alternatives are not only encouraged through present carbon prices but also through expectations about future carbon tax increases. Tvinnereim and Mehling’s review of the record of several prominent carbon pricing strategies suggest that they have helped realize limited opportunities for innovation and system-wide transformation. Rather, current trajectories and emission reductions deviate little from business-as-usual scenarios, even in the case of Sweden’s $140 (USD) carbon price for the transport and building sectors. Others have observed similar patterns which suggest that, in practice, carbon pricing strategies tend to promote the optimization of established business models and technologies but “neglect more fundamental system change necessary for deep decarbonization.”

Richard Rosen points out that according to World Bank’s Carbon Pricing Dashboard, the estimated average carbon price for the almost 20% of worldwide carbon dioxide emissions that occurred within carbon pricing schemes in 2018 was only about $7.43 per ton of CO2, hardly enough for any consumer of fossil fuels, even businesses, to notice such a small price increase in the actual energy products they purchase. This very low average carbon price is certainly not high enough to get many people or businesses to significantly reduce their carbon emissions, or even to react at all.

Richard Rosen also points out the difficulties of the concept of a uniform global carbon tax. The same tax level (e.g. $100 per tonne of CO2) would have a very different macroeconomic impact in a rich country versus a poor country. In a rich country, a tonne of CO2 emissions might cost only two hours of a worker’s wage, whereas in a poor country this could easily represent two weeks’ wages or more. Thus, the incentive to use less fossil fuels would be far stronger in poor countries, so much so that even a moderate carbon tax such as $100 per ton might cause major disruptions to their economies and family livelihoods even though the per capita consumption of fossil fuels in poor countries is much lower than in rich countries. Thus, in poor countries, carbon emissions may not be reduced much per person in spite of the stronger financial incentive to do so. “One issue, then, that must be discussed when discussing the possible merits of carbon taxes, is to what extent can poor countries seriously consider implementing a carbon tax anywhere near the higher level of a carbon tax that might be established in rich countries. And if doing this would be impossible, would this allow global corporations to escape paying much of a carbon tax by moving production from rich to poor countries, even more than they have done already, among other unintended consequences?”

There is definitely a role for carbon taxes but in themselves they fail to address and provoke the need for fundamental transformation and an integrated approach to that transformation. There are also a range of difficult political realities regarding their implementation and the potential impact on poorer members of national and international communities.

CONCLUSION

The driving force of growth of capitalism, it’s innate and unquestioned imperative, is growth. Growth of revenue, growth of profits, growth of markets, growth of market share. People who work in capitalist enterprises, from CEOs to junior salesmen are given growth related targets, people who advance in advance to senior positions in these organisations do so because they have grown income, profits, market share etcetera.

Capitalist organisations and groupings accumulates political power and influence commensurate with their economic heft and importance. It’s estimated that $3.5billion was spent on political lobbing in the USA in 2020. The real figure is probably much higher. This is why fossil fuels and environmentally damaging parts of the agricultural sector continue to receive huge subsidy from governments, governments that regularly mouth platitudes about the need to fight climate change. The recipients of the subsidy continue to pursue policies of growth and profit maximisation irrespective of the damage inflicted on the environment because that is the essence of what they do; corporates induce crowd-like behaviour and transmit their values to employees, the latter come to identify their well-being and future with that of the company, companies that act like Canetti’s crowd.

“Once in being it spreads with the utmost violence, it always wants to go on growing and there are no inherent limits to its growth.” Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power.

To effect real change and the transformation necessary to save the planet we need to challenge the vested interests of corporate power and the political authority with which it is intimately connected, the above analysis provides plenty of examples. We need to reset the purpose of economic activity and challenge the growth imperative. Sustainability policies need to be coupled with redistribution of income and wealth, nationally and between nations with particular focus on justice for the developing world and emphasis on collaboration rather than political/economic competition.

The attitudes and culture perpetuated by capitalism such as the heedless consumerism that drives the fashion industry, the greed that places 10% of world GDP into tax havens, the indifference to the deaths of the workers in Rana Plaza that made our cheap t-shirts in hideous conditions, the willingness to accept more pollution as long as it shaves 10 minutes of your car journey; these must also be fought in the interests of building a new society but not one that completely obliterates the individual.

The working of the mythical “free market” cannot be allowed to lead the fight for survival no more than can the blinkered greed that dictates its priorities and rationalisations. We need coherent, integrated plans to escape this crisis that recognise the comprehensive transformation required.

We need the collective harnessing of resources in a coherent manner aimed at achieving outcomes that enable us to survive, maximise the common good and pursue the priorities of protecting the most vulnerable and elevating the most oppressed; in short, socialism or extinction.

Further Reading

https://www.insulatebritain.com/breaking-industry-experts-back-insulate-britain-s-demands

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-51977625

https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions-from-transport

https://cuesa.org/learn/how-far-does-your-food-travel-get-your-plate

https://ourworldindata.org/emissions-by-sectorhttps://stories.mightyearth.org/amazonfires/index.html

https://www.ft.com/content/0d38e8d3-3f20-4818-8751-740d05f8ac13

https://khni.kerry.com/news/the-environmental-impact-of-sugar-reduction/

https://wwfeu.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/sustainablesugar.pdf

https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2019/09/23/costo-moda-medio-ambiente

https://www.ft.com/content/46d4727c-761d-43ee-8084-ee46edba491a

https://www.pnas.org/content/117/16/8664

https://www.ineteconomics.org/perspectives/blog/carbon-taxes-a-good-idea-but-can-they-be-effective

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/195292956.pdf

https://www.statista.com/statistics/257337/total-lobbying-spending-in-the-us/