August 1945 was a momentous month for Koreans. At midnight on the tenth day of that month, two US army colonels, Dean Rusk and Charles Bonesteel were ordered by John J. McCloy, assistant secretary of war, to find a place to divide Korea to temporarily partition the peninsula into separate US and Soviet occupation zones to accept the Japanese surrender. They chose the thirty-eight parallel because it would include Seoul, Korea’s capital, in the US zone. In 1910, the Japanese had formally integrated Korea into their Empire of the Rising Sun. They favoured the large landlords and subjected other Koreans, the vast majority, to various forms of oppression, including coerced labour and sexual slavery. Some Koreans collaborated with the Japanese, joining the colonial police force, the Korean National Police (KNP), which enforced a tyrannical rule over the country. Others enlisted in the Japanese Imperial Army, taking Japanese names, and in some cases, helping hunt down Korean resistance fighters. Now the Japanese were on the verge of defeat, tottering under the combined assault of the United States and the Soviet Union.

Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had given his commitment to US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill at the Yalta conference of February 1945 to enter the war in the Pacific three months after the end of the war in Europe. The war in Europe ended on May 8, 1945. Exactly three months later, on August 8, Stalin sent Soviet forces sweeping into Manchuria and Korea, initiating the largest land battle of the Pacific War. Within days, eighty thousand Japanese soldiers were dead, and six hundred thousand had surrendered, at the expense of thirty thousand Soviet fatalities.

In the US-dominated historiography of WWII, Washington decided atomic devastation on two militarily insignificant Japanese cities, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which constituted the final blow against the Japanese. However, this narrative completely ignores the role of the Soviet Union. It was the Soviet intervention that delivered the coup de grace to Japan. Earlier, Japan’s leaders had recognized that defeat was only a matter of time and that their only hope was to engage Soviet assistance to sue for peace and to obtain some minor concessions, above all immunity for their emperor. With that hope dashed by the Soviet declaration of war, they knew that all was lost. Their situation had deteriorated from desperate to hopeless. They surrendered unconditionally seven days after the start of the Soviet intervention, on August 15, a day that went down in history as “Victory over Japan Day” or “V-J Day.”

US forces would not arrive in Korea until September 8, a full month after the Soviets arrived in the north of the country, and three weeks after the Japanese surrendered. For three weeks, from VJ-Day forward, no undefeated occupation force was in Korea south of the thirty-eighth parallel. During this period, Koreans in the south were able to take control of civic administration, by their efforts. Koreans also took civic administration into their own hands in the north, encouraged by Soviet occupation authorities. By September 6, Koreans had organized a peninsula-wide network of local provisional governments and proclaimed a Korean People’s Republic - the first independent Korean government since Japan had incorporated Korea into its Empire of the Rising Sun, thirty-five years earlier. But Korean independence was not last long.

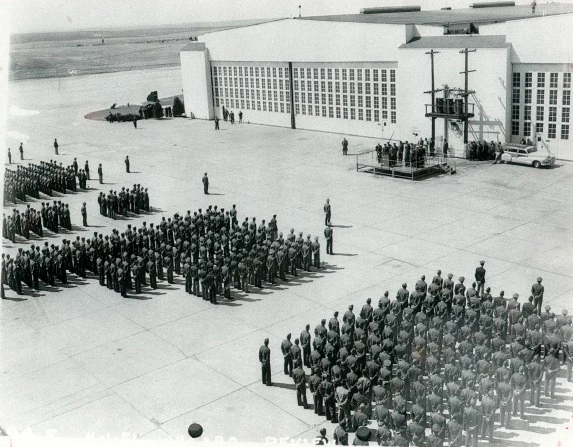

The next day, US General Douglas MacArthur, the commander-in-chief of US forces in the Pacific, issued a proclamation, notifying the Korean people that the United States would not recognize the newly-proclaimed republic. Instead, US forces would “establish military control over Korea south of 38 degrees north latitude and the inhabitants thereof.”

The commander of the US occupation forces, General John R. Hodge, became the military governor of the US zone. Hodge had a choice: allow the Koreans, through their newly created republic, to take over the reins of government, or retain the Japanese and their Korean collaborators in their positions in the colonial administration. He chose the latter. “We could [have] come as liberators,” the American journalist Anna Louise Strong lamented, “but we chose instead to come as conquerors.” It was the same throughout East Asia. The journalist Israel Epstein observed that:

British and Dutch troops landing to ‘liberate’ Java did not disarm conquered enemy units but ordered them to cooperate in subduing the local population, which had formed a government to rule itself . . . French forces in Indo-China, again with British support, employed Japanese soldiers against the independent Vietnam government. The British in Malaya allowed the Japanese garrison to keep a considerable part of their arms for ‘self-defence’ and began to hunt down the wartime anti-Japanese guerrillas there.

The United States came as a conqueror because Washington wanted to incorporate Korea into the undeclared US Empire and the aspirations of Koreans, yearning for freedom, happened to oppose this US project. “Koreans longed for independence after suffering four decades of Japanese rule,” wrote US historian Melvyn P. Leffler, but the administration of US President Harry S. Truman “feared that . . . radical nationalists or communists would take control.” The US government, therefore, decided to deny Koreans the right to govern themselves. Instead, Washington brought conservatives and pro-Japanese collaborators to power, to establish a US-superintended hierarchy, with the Americans ensconced at the top, Korean elites and quislings immediately below them, and the bulk of Koreans at the bottom, precisely where they had been under Japanese rule. Koreans despised the new US-imposed imperial order, as much as they had despised the Japanese equivalent, and opposed it as fervently as they had opposed the hated Japanese. In the war that would develop between a new colonial master and liberation forces, Koreans who had collaborated with the Japanese would play an important part, reprising their role as kapos in an imperial prison, now under the supervision of a new warden.

At the end of 1945, Hodge and his advisers created a four-point plan to destroy the movement for independence in southern Korea. First, they set up an army, staffed by Koreans who had served as officers in the Japanese army, intending to isolate the south from the independence movement in the north. Second, the KNP, the instrument of violence the Japanese had used to suppress opposition to their rule, was rebuilt. Where the KNP’s original mandate had been to crush opposition to the Japanese occupation, the organization’s new mandate was to quell opposition to the successor occupation of the United States. Third, the occupation government’s alliance with right-wing, collaborationist forces was strengthened. And fourth, opponents of the new regime were rounded up and jailed. This amounted to a declaration of war on the Korean People’s Republic. By 1948, Hodge’s war on the independence movement in the south had driven the movement’s supporters into graves, into jail, underground, or to the north. “Germany was built up by Hitler to fight communism,” Hodge had observed. But the US military governor was building a parallel state in Korea to achieve the same anti-left goals that had animated the Nazi project in Germany. Hodge and his successors, a string of South Korean strongmen, belonged to the same class as Hitler, Mussolini, Franco, Pinochet and Suharto — dictators whose chief political goal was to combat communism and all other real or perceived threats to the established capitalist order.

In the meantime, a provisional government was established in the Soviet occupation zone, with Kim Il Sung as its president. Kim was neither a puppet installed in a North Korean Soviet satellite state by Joseph Stalin, as US propagandists would have it, or an imposter who stole the name of a famous anti-Japanese guerrilla, as South Korean propagandists would allege. Instead, he was a genuine Korean patriot who devoted his life to achieving Korea’s freedom, “recognizably a hero,” as the US historian Bruce Cumings called him, who had fought against the Japanese for more than a decade.

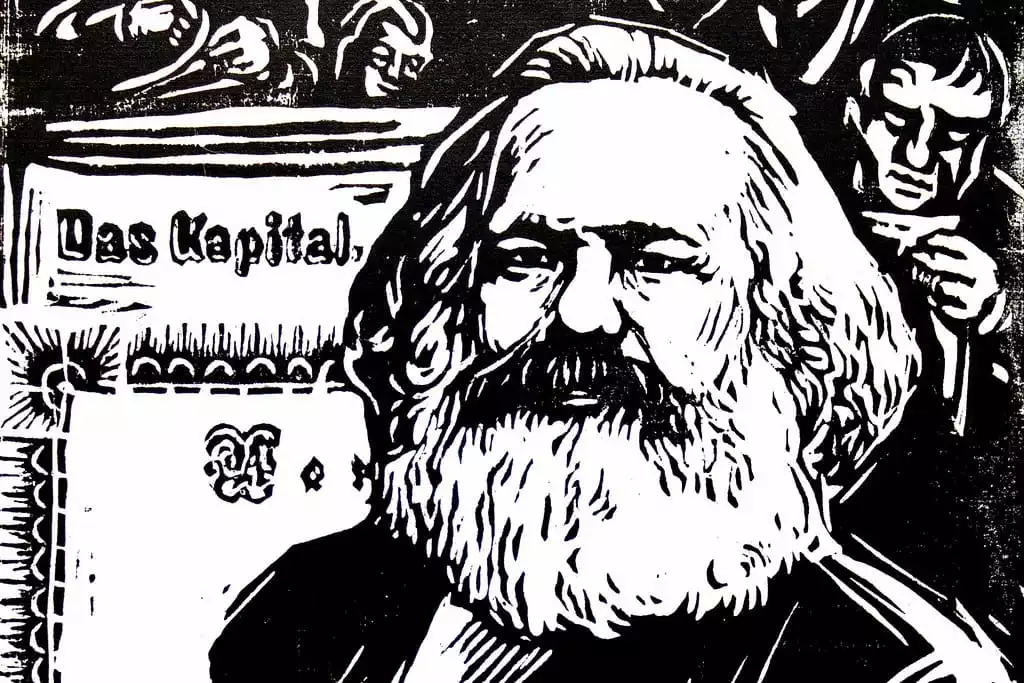

As a high school student, Kim Il Sung joined an underground Marxist group, and read the works of Marx and Lenin. This led in 1929 to his arrest and incarceration for several months by Japanese colonial authorities. After Japan created a puppet state in the northern Chinese region of Manchuria, bordering Korea, in 1931, naming it Manchukuo, Kim joined the Chinese Communist Party and went underground to organize guerilla opposition to the Japanese. He founded his first guerrilla unit in the spring of 1932, with the long-term objective of liberating Korea.

So significant a figure was Kim that the Japanese army established a special division to hunt him down, headed by General Nozoe Shotoku. One of Nozoe’s top officers was a Korean traitor, Kim Sok-won, who had joined the Japanese Imperial Army and taken the Japanese name Kaneyama Shakugan. Kim Sok-won would later become the commander of South Korean forces on the thirty-eighth parallel, playing a signal role in the events surrounding the beginning of the Korean War in 1950. But Kim Sok-won was not the only traitor who worked to hunt down Kim Il Sung and other Korean resistance fighters. Another was Park Chung-hee, who joined the Japanese Imperial Army and likewise adopted a Japanese name, Takagi Masao. As a Lieutenant in the emperor’s military, he was assigned to a counter-insurgency unit to hunt down his countrymen. Park later became South Korea’s president and is the father of Park Geun-Hye, the disgraced former South Korean president, who was forced to resign in 2017 in a scandal. Her term in office overlapped that of North Korea’s leader Kim Jong Un, Kim Il Sung’s grandson.

Kim’s provisional government undertook a series of egalitarian reforms. A sweeping land reform law was implemented, redistributing land to the tiller. Child labour was outlawed, and the working day was set to eight hours. All industry belonging to the Japanese and collaborators was nationalized. And an economic plan was formulated to convert the economy, which had been tailored to meet the needs of the Japanese, to meet the needs of Koreans.

South of the thirty-eight parallel, Washington launched a vicious anti-insurgency war to exterminate opposition to the US suppression of the Korean People’s Republic. By December 1947, the US-controlled KNP had rounded up and jailed tens of thousands of leftists. The magnitude of the opposition to the US occupation regime was so great that the KNP’s jails could not hold all the dissidents the KNP arrested. To handle the excess, concentration camps, euphemistically denominated as ‘guidance camps’, were established to immure the 70,000 leftists who exceeded the capacity of the overcrowded prisons, already teeming with 30,000 communists. Roger Baldwin, the head of the American Civil Liberties Union, visited Korea in May 1947, reporting that the south “is literally in the grip of a police regime and a private terror.” One prison he toured contained one thousand inmates who had been jailed for organizing unions and strikes. In Bruce Cumings’ assessment, the Americans had “created one of the worst police states in Asia.”

Despite agreeing with the Soviets to terminate their joint occupation of Korea within five years, the Americans had no intention of withdrawing from their occupation zone. A presence on the Korean peninsula offered too many attractions to a US state determined to exercise hegemony on a global scale. WWII had plunged Washington’s defeated Japanese rival into an economic abyss that was incubating Japan’s communist movement, much to Washington’s consternation. US officials believed that if Japan could be reconnected to its former colonies, including Korea, its economy could be revived, which would help to eliminate the threat of a communist take-over in Japan. What’s more, a continued US military presence on the peninsula would facilitate the goal of containing and possibly rolling back communist movements in nearby China, Russia, and North Korea.

Rather than working with the Soviets and Koreans to organize national elections for a pan-Korean government, the Americans decided to carry out elections in their zone, under the auspices of the United Nations, which, at the time, was dominated by the United States and its allies. Washington’s objective was to form a South Korean state under US control to perpetuate US influence on the peninsula. To pre-empt the US plan, Koreans organized a National Unity Conference at Pyongyang, which met three weeks before the scheduled date of the US-orchestrated poll. The conference included delegates from both the Soviet and US occupation zones, who declared themselves unalterably opposed to the impending election, denouncing it as a manoeuvre by the United States to politically partition Korea by creating a government in the south. In place of the US scheme, the conference proposed the immediate withdrawal of the two occupation armies, a national political conference to organize a provisional government to draw up a constitution, and elections to form a national government. US officials ignored the Koreans’ proposal.

Much to Washington’s surprise, even most Korean conservatives, who US officials counted on to back their scheme, expressed opposition to what appeared to them to be an obvious device to permanently partition their country. Parties of the left and centre, and even some of the right, boycotted the election. All the same, the Americans obstinately pushed ahead. Leaving nothing to chance, the UN committee overseeing the elections, stuffed with US allies, allowed the KNP, run by US occupation authorities and dominated by Koreans who had collaborated with the Japanese, to organize the voting. Through these illegitimate means, Washington midwife the birth of a pro-US, anti-communist police state with Syngman Rhee—a man who had spent more than three decades in the United States hobnobbing with America’s untitled nobility—as president. The state, founded on August 15, 1948, would be called the Republic of Korea, (ROK) and informally be known as “South Korea.”

The Rhee government formally superseded the US military government, but US officials continued to govern in the shadows. Secret protocols granted the Pentagon indefinite command of the South Korean military and police. Even today, the United States retains formal operational control of the South Korean military in wartime. A commander of US forces in Korea, General Richard Stilwell, has called this the “most remarkable concession of sovereignty in the entire world.”

With the political partition of Korea now a fait accompli, there was little choice for Koreans living in the Soviet occupation zone but to declare their state, which they did three weeks later, on September 9, 1948. A day later, the newly formed Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), or North Korea, asked the Soviet Union and the United States to withdraw their military forces from all of Korea. The Soviets complied, completing their exit from the peninsula by December 25. Washington ignored the request and has maintained an unbroken military presence on the Korean peninsula since September 1945.

What would have happened had the United States and the USSR refrained from occupying Korea and allowed Koreans to direct their liberation? The answer is clear from what did happen up to the point US forces arrived on the peninsula. Koreans purged the Japanese and their collaborators from the civil administration and brought it under their control, began land reform, and met to organize a central government and proclaim a republic. The US historian Frank Baldwin emphasized that in “1945 Koreans would have worked out a new destiny if the US and Soviet Union had not intervened. That destiny almost certainly would have been a leftist, perhaps a communist, government.” What would have happened if the United States and the Soviet Union had accepted the Japanese surrender and then quickly left Korea? Bruce Cumings claims that “a leftist regime would have taken over quickly, and it would have been a revolutionary nationalist government.” But neither of these potential outcomes materialized. Instead, the Republic of Korea was established, headed by a fanatical anti-communist and US proxy who believed not only that his state had sovereignty over the entirety of the Korean peninsula, but also that it was his duty to bring all of its declared domains under his control. Rhee frequently promised to undertake a “northern expedition” to “recover lost territory,” and in the summer of 1949, it was his army that started to provoke fighting along the thirty-eighth parallel.

On the other side of the parallel, Kim Il Sung headed a state that had a legitimate claim to represent all Koreans. He had the moral authority of having been the leader in the Korean anti-colonial struggle in Manchuria. He commanded significant support among Koreans in the north, on the strength of his considerable charisma and organizational abilities. Syngman Rhee, on the other hand, had been handpicked by US masters and was brought to power in a boycotted election, held after the US occupation government led a three-year-long campaign to exterminate the opposition. It was clear to most observers that, in a fair national election, Kim Il Sung would be elected president.

Kim believed it was his patriotic duty to recover the southern territories held by Rhee’s illegitimate US puppet government to unify the country. His forces also provoked fighting along the zonal division line established by the Americans. Throughout 1949, there were numerous skirmishes between ROK and DPRK troops, but most skirmishes were instigated by the army of Syngman Rhee. Washington regarded Rhee as a hothead and worried that his provocations of Kim’s forces would escalate into an all-out war. US planners recognized that Rhee lacked popular support, and would likely take a drubbing if he launched his promised drive to the north. As a consequence, the Pentagon declined to supply him with tanks and warplanes.

A declassified February 1949 CIA report had recognized “an inherent Korean sentiment against foreign interference,” that is, against the US presence on the peninsula. It also noted that Rhee’s government faced a “strong and efficient” Korean patriot underground. Hadn’t Hodge, and after him, Rhee, spent the four years since the arrival of US forces on the peninsula rounding up leftists, immuring them in concentration camps, and fighting guerrillas in the countryside? Despite their efforts, the resistance continued. Rhee’s government was the manifestation of the foreign interference the CIA observed and knew to be widely opposed by Koreans. So long as an anti-communist US puppet state existed, there would be a patriot underground. And that meant the ROK would always be vulnerable to a fifth-column liberation movement.

On June 25, 1950, North Korean forces crossed the imaginary line Rusk and Bonesteel had drawn five years earlier to separate US and Soviet forces. According to the DPRK, ROK forces crossed the line first and were met by an immediate DPRK counter-offensive. But in a report issued on June 26, the UN blamed the outbreak of the fighting entirely on North Korea. The report was based on US and South Korean sources - hardly unbiased. In this way, US officials were able “to define the war as they saw fit, making their official story of what happened definitive and lasting,” as historian Bruce Cumings put it. However, it is not clear which side crossed the thirty-eighth parallel first. While the reigning view, reflecting US ideological hegemony, is that the DPRK initiated a general invasion, the matter of who initiated the fighting remains sub judice in the court of scholarly research.

The ROK collapse was immediate. Syngman Rhee and his inner circle fled, soon followed by the South Korean army. The outcome was predicted by the CIA, which in a March 1948 secret memorandum concluded that “the Extreme rightists under Rhee . . . corrupt, reactionary and oppressive . . . would be incapable of withstanding ideological and military pressure from North Korea.” North Korean forces liberated Seoul within three days. By late August, Kim Il Sung’s forces had freed nine-tenths of the peninsula from the grip of “the unpopular and unreliable” Rhee regime, as the CIA had described him. South Korean and US forces held on only in Pusan, on the southeast tip of the peninsula.

To rescue its Korean marionette, the United States sought and obtained a UN mandate to intervene in manu militari in Korea. The authorization of the US-dominated world body was secured in the absence of the USSR, which was boycotting the Security Council for its refusal to recognize the People’s Republic of China’s claim to China’s seat on the council, which was still held by the Kuomintang regime based in Taiwan.) In reality, US forces were already present on the peninsula and engaged in combat by the time the UN gave its blessing; the authorization merely provided an ex-post-facto justification for US intervention.

The US-led force fought under the banner of the UN flag and relied on token troop contributions from UN members to create the impression that it represented an international coalition. In reality, it was mainly US forces under US command but shrouded in UN camouflage. The commander, Douglas MacArthur, reported directly to the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, not to the United Nations.

The first phase of the war, the war for the south in the summer of 1950, came to an end on September 15 when MacArthur landed his forces at Inchon, the port of Seoul, halfway up the peninsula. Had the United States not landed an invasion force, the North Koreans would have quickly won the war, and the lives of millions would have been spared. What’s more, Koreans would have formed the first independent government since 1910, save for the short-lived Korean People’s Republic, which the United States had refused to recognize. However, MacArthur’s amphibious invasion at Inchon cut off North Korean forces from their base in the north. To avoid annihilation, DPRK troops melted into the countryside and retreated behind the thirty-eighth parallel. The UN resolution authorizing US intervention had demanded that Kim’s forces pull back behind that demarcation line. Therefore, with the North Korean withdrawal from the south, the matter should have been resolved, and MacArthur should have held the line there. But on September 11, four days before landing at Inchon, MacArthur had obtained Truman’s authorization to launch an offensive north of the thirty-eighth parallel. US forces captured Seoul on September 25, and five days later pushed into the north, across the dividing line drawn five years earlier.

MacArthur’s northward drive to the Yalu River, one of two riparian boundaries separating Korea and China, brought the Chinese into the war. On October 25, Chinese leader Mao Tse-Tung deployed to Korea an army of 300,000 Chinese to arrest the US advance. Mao designated the army a volunteer force, calling it the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army, to avoid a formal clash with the United States, but the ‘volunteers’ were in reality members of the People’s Liberation Army. Thus began what some have called the Sino-American War. The Chinese virtually eliminated the remnants of the South Korean army and drove US forces back across the thirty-eighth parallel by December.

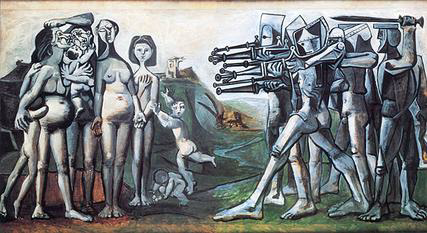

Stunned by the collapse of MacArthur’s forces at the hands of a lightly armed army of peasants, Truman declared a national emergency, and MacArthur called for a nuclear strike, importuning the president to authorize the use of fifty nuclear bombs to reverse the setback. Truman declined. But for the next two years, the United States set about producing, by conventional means, the equivalent destruction of many nuclear attacks. MacArthur used US bombers to create a wasteland, ordering the use of incendiaries to burn to the ground every city, village and factory, between the thirty-eighth parallel and the Chinese border. US warplanes dropped more bombs on North Korea than the United States had dropped in the entire Pacific theatre during World War II. The extent of the physical destruction was horrifying. It is not certain that every building over one story was destroyed, as some have claimed, but it is clear that the US Air Force created a wasteland. By the end of the war, only two modern buildings remained standing in Pyongyang. Dean Rusk, when he was the Assistant Secretary of state for Far Eastern Affairs, acknowledged that the Americans bombed everything “that moved in North Korea, every brick standing on top of another.” By the autumn of 1952, MacArthur’s ambition to create a wasteland had been realized. No city, town or building of significance north of the thirty-eight parallel remained to be incinerated. So, US forces targeted irrigation dams on the Yalu River. Five reservoirs were destroyed by US bombers, inundating thousands of acres of farmland, flooding towns and destroying a vital source of sustenance for millions of North Koreans.

Estimates of the number of fatalities produced by the war range from three million to over four million, with Koreans accounting for two million to three million deaths. Chinese fatalities ranged from an estimated six-hundred thousand to one million. US deaths were a comparatively insignificant thirty-seven thousand, one to two per cent of the total. Given that in 1950 Korea comprised approximately twenty million people, the war destroyed ten to fifteen per cent of its population, equal per capita to the number of Soviet citizens killed during WWII. Roughly three per cent of the Japanese population perished in the Pacific War, much lower than the Korean fatality rate in the 1950-1953 holocaust.

US officials have exhibited no restraint ever since in threatening to carry out additional demographic holocausts against North Koreans. Wesley Clark, a US general who commanded NATO forces in Europe and led NATO’s air war on Yugoslavia in 1999, threatened North Korea’s leaders, boasting that the United States could cause their country to “literally cease to exist.” In 1995, Colin Powell, who had served as chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff and later served as US Secretary of State, warned Pyongyang that the United States had the means to turn North Korea into “a charcoal briquette.” In 2017, US Senator John McCain, chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee, warned the DPRK that the price of acting “in an aggressive fashion . . . will be extinction.” More recently, President Donald Trump similarly conjured up the possibility that Washington might have “no choice but to destroy North Korea.”

The United States bears the main responsibility for the millions of lives destroyed during the Korean War. At every point, US leaders made decisions that guaranteed that the mountain of corpses would pile ever higher. First, Washington made war inevitable by politically partitioning the country. Then, when the 1950 conflict broke out, the United States immediately acted to prevent an imminent North Korean victory, which would have ended the conflict. Instead, the United States intervened on behalf of “extreme Rightist forces” acknowledged by the CIA to be “unpopular” as well as “corrupt, reactionary and oppressive” and unable to stand on their own. Third, when North Korean forces withdrew north of the thirty-eighth parallel, Washington could have chosen to break off hostilities, as the UN resolution authorizing the use of force indicated it should. But MacArthur pushed forward, intent on destroying the infant North Korean state and establishing a US puppet regime over the entire Korean peninsula. Fourth, when Chinese forces pushed the United States back over the thirty-eighth parallel, Washington could have agreed to end the war. Instead, it fought on for two more years, before finally accepting restoration of the status quo ante. In those two years, the United States burned North Korea to the ground.

As a civil war, the war between the two Korean states was a quarrel over how to organize the social, political and economic life of the peninsula on whose soil existed a single nation, but two states. At the heart of the debate was the question of equality. Are people, as individuals, and peoples, as nations, equal, and should they enter into associations based on mutual benefit, or are some people or nations, such as Americans and the United States, destined to lead others? Should the exploitation of man by man, be prohibited or welcomed? Should the country be aligned with, and integrated into, the US Empire, or allowed to be independent? And who should govern - Koreans who had collaborated with the Empire of the Rising Sun and were just as eager to collaborate with the American Empire, or those who fought against the Japanese and insisted on independence from the Americans?

Contrary to the received view, the civil war began not in 1950, but in 1932, when Kim Il Sung formed his first guerrilla unit to fight the Japanese, and Koreans of another stripe, such as Park Chung-hee, chose another route, joining the Japanese army to enforce colonial rule over their compatriots. The Korean War was, thus, a civil war fought to settle scores between these two groups – Korean patriots led by Kim and Japanese collaborators who, after the defeat of Japan, and under American auspices, were to morph into the elite of South Korean society.

The end of open hostilities from 1950 to 1953 was secured by an armistice, or cease-fire, not a peace treaty. North Korea has repeatedly offered to sign such a treaty, but the United States has just as frequently rejected North Korea’s offers. As for South Korea, it even refused to sign the armistice agreement ending open hostilities. Technically, then, the United States and South Korea remain at war with North Korea.

US policy from the moment of North Korea’s birth has been to bring about the state’s demise. This policy has remained intact, through a succession of Democratic and Republican administrations. A policy of permanent peaceful co-existence, and not just one that is tactical and temporary, is not in the cards. Imperialists, Mao once observed, will never lay down their butcher knives and become Buddhists. And US officials have never contemplated conversion to pacifism.

As a consequence, Korea remains divided. Tens of thousands of US troops continue to occupy the south, successors to a preceding Japanese occupation. The South Korean military remains under the command of the Pentagon, as it has from the very first moments of its birth. And the US Empire - unprecedented in scope and reach - remains undiminished in its resolve to smash North Korea, one of only a handful of states representing an alternative – a ‘counter system – to capitalism, and one of the few countries prepared to rejecting US imperialism and defying US aggression.

If you are a socialist, We need you now!✕

We are proudly biased towards Anti Capitalist, Anti Imperialist, Anti fascist! We believe we don’t need to mention you the importance of marxist magazine in this era! We are depending on our comrades only! Make an investment of $2.5/m in making a quality journal inclined to Marxism Leninism! Your one potential subscription helps us to maintain our global team! Subscribe and get access of all exclusive content available at the magazine section!