The ideas propagated by bourgeois economists and the right-wing on taxation, particularly those that associate low taxes on the rich and on corporates with economic growth, are nonsense: the following shows why.

It will additionally cover some of the implications of low marginal taxes on the wealthy for the workings of the economy.

Overview:

In 1988 I was working in the financial sector and was listening to Nigel Lawson’s budget speech on the dealing floor of a London Merchant Bank. There was a huge cheer as Lawson announced a cut in the top rate of tax from 60% to 40%

In the following days, weeks months and years, did those cheering stockbrokers, market makers, merchant bankers, and analysts work any harder as a result of this cut in taxes and take more risks? Were their animal spirits unleashed?

No. they were all pretty motivated ambitious people who wanted to rise up the corporate ladder, the tax cut didn’t make them work harder; the risks they took were a function of the targets they were set nothing to do with government tax cuts.

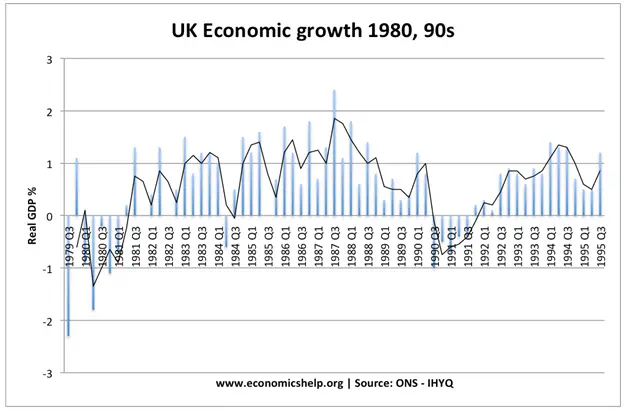

Did it lead to greater economic growth? No, see the graph attached. After Q1 of 1988 the UK economy’s performance actually started to decline compared to the preceding years. There were a number of contributory factors, but it’s clear from the data that the higher rates of tax that applied before 1988 did not act as a serious constraint on growth.

Nor have they ever.

The Evidence on Personal Income Tax

Much of the quality research in this area has been done in the USA and this article will reflect that bias, the results will have applicability beyond the USA.

A 2013 study by the non-partisan Congressional Research Service (CRS), Congress’s policy research arm, examined tax rates and economic growth since World War II. The study concluded:

“changes over the past 65 years in the top marginal tax rate and the top capital gains tax rate do not appear correlated with economic growth. The reduction in the top statutory tax rates appears to be uncorrelated with saving, investment, and productivity growth. The top tax rates appear to have little or no relation to the size of the economic pie.”

From the summary:

“Throughout the late-1940s and 1950s, the top marginal tax rate was typically above 90%; today it is 35%. Additionally, the top capital gains tax rate was 25% in the 1950s and 1960s, 35% in the 1970s; today it is 15%.

The real GDP growth rate averaged 4.2% and real per capita GDP increased annually by 2.4% in the 1950s. In the 2000s, the average real GDP growth rate was 1.7% and real per capita GDP increased annually by less than 1%.

This analysis finds no conclusive evidence… to substantiate a clear relationship between the 65-year reduction in the top statutory tax rates and economic growth. Analysis of such data conducted for this report suggests the reduction in the top tax rates has had little association with saving, investment, or productivity growth.

https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/79450/CRS_Taxes_and_the_Economy.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

And see this table showing the top 20 years for US growth:

TOP 20 YEARS FOR GDP AND TAX RATE OF TOP BRACKET

Year - GDP Change - Top Tax Rate

1942 - 18.9% - 88.0%

1941 - 17.7% - 81.0%

1943 - 17.0% - 88.0%

1936 - 12.9% - 79.0%

1934 - 10.8% - 63.0%

1935 - 8.9% - 63.0%

1940 - 8.8% - 81.1%

1950 - 8.7% - 84.4%

1951 - 8.1% - 91.0%

1939 - 8.0% - 79.0%

1944 - 8.0% - 94.0%

1984 - 7.3% - 50.0%

1955 - 7.1% - 91.0%

1959 - 6.9% - 91.0%

1966 - 6.6% - 70.0%

1965 - 6.5% - 70.0%

1962 - 6.1% - 91.0%

1964 - 5.8% - 77.0%

1973 - 5.6% - 70.0%

1978 - 5.6% - 70.0%

(Source of this table- politicsthatwork.com)

CURRENT TAX RATE OF THE TOP BRACKET- 37%

There are a variety of factors at play behind the very high growth rates shown in these years, but at the very least, the data proves beyond a doubt that much higher taxes on the rich are compatible with much faster economic growth than we have today.

Corporate Tax

There is no correlation and no identifiable causation between corporate tax rates and corporate profits. Neither the level of corporate taxes nor changes in corporate taxes have any effect on corporate profitability. The same holds true for either effective corporate tax rates or the top corporate tax rates.

Consequently, there is also no relationship between lower corporate tax rates and higher economic growth. The United States currently has one of the lowest corporate tax rates in its history, yet economic growth is significantly below historical averages.

https://blogs.cfainstitute.org/investor/2017/04/04/

Changes in corporate tax rates don’t stimulate the economy either. In the immediate aftermath of the tax hikes in the 1950s, real US economic growth accelerated above 8%. Following the Reagan tax cuts, real economic growth hovered around 4% without receiving much of a boost.

Lowering the corporate income-tax rate would not spur economic growth. The analysis in this report by the Economic Policy Institute found no evidence that high corporate tax rates have a negative impact on economic growth (i.e., it found no evidence that changes in either the statutory corporate tax rate or the effective marginal tax rate on capital income are correlated with economic growth).

https://www.epi.org/publication/ib364-corporate-tax-rates-and-economic-growth/

The Value of High Marginal Taxes on Top Earners

Not only does the above demonstrate that high taxes on the wealthy and corporates do not constitute a barrier to economic growth, many of the figure and correlations suggest a positive relationship between such taxes and economic growth.

Two main factors at play here:

1. Wealthy people tend to spend proportionally less of their income, tax policies that take money from the wealthy to finance government expenditurewill tend to stimulate the economy as opposed to leaving the money in the hands of people who would invest it in shares, commodities or some other scheme. This is one of the factors behind the IMF’s belated recognition that inequality is not good for growth.

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/feb/26/imf-inequality-economic-growth

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/jan/07/imf-boss-says-raise-taxes-on-the-rich-to-tackle-inequality

2. Allowing top earners to keep more of their money means they are more likely to (i) award themselves excessively high remuneration through high salaries and/or share-related reward schemes, these rewards utilise company profits in pursuit of their enrichment rather that investment in innovation and the economy’s future, and (ii) the wealthy are able to build up a super-surplus of funds that they invest in the stock and other securities markets, asset prices become inflated, commodities prices are heightened by speculation and the resultant increase in food prices pressurises the poor, the booming markets eventually collapse and the economy needs to be rescued, with government money.

The latter summarises what happened to the global economy in 1929 and 2008. Indeed, fear of a repetition of 1929 was one of the factors behind America’s embrace of high marginal rates on top earners even before the outbreak of WW2, see the table above comparing marginal taxes and growth rates.

Effects of High CEO Pay

CEO compensation in America is very high relative to typical worker compensation (by a ratio of 278-to-1 or 221-to-1);that ratio was 20-to-1 in 1965 and 58-to-1 in 1989.

CEOs are even making a lot more—about five times as much—as other earners in the top 0.1%. From 1978 to 2018, CEO compensation grew by 1,007.5%, far outstripping S&P stock market growth (706.7%) and the wage growth of very high earners (339.2%).

In contrast, wages for the typical worker grew by just 11.9%

Marginal tax rates for top rate tax earners and corporations dropped dramatically in the 1980s. High pay increased as did the incentive for managers to use the corporate surplus to award themselves and shareholders through a succession of short-term, financialised schemes rather than using the surplus to invest in the future.

The results:

• Head of Blackstone Asset managers in a 2015 open letter accused corporate bosses of underinvesting in innovation, skilled workforces or essential capital expenditures necessary to sustain long term growth

• Harvard Business Review 2018: “investment low given the extraordinarily low-cost of equity and debt, and the amount of cash on corporate balance sheets. Measured against GDP, corporate after-tax profits are almost double what they were 25 years ago — and higher than at any time since World War II — yet business investment as a share of GDP only rose by 13% over the same period,”

• And recent research by Germán Gutiérrez and Thomas Philippon of New York University suggests growing business concentration,and short-term thinking on the part of investors have all contributed to firms “spending a disproportionate amount of free cash flows buying back their shares,” fostering an environment of “investment-less growth.”

https://www.nber.org/papers/w22897

The growth of the use of stock buy-backs since a change in legislation that legitimised them in the mid 1980s has been extraordinary and highlights the issue:

“It can make sense for a company to leverage retained earnings with debt to finance investment in productive capabilities that may eventually yield product revenues and corporate profits. Taking on debt to finance buybacks, however, is bad management, given that no revenue-generating investments are made that can allow the company to pay off the debt…..

Buybacks’ drain on corporate treasuries has been massive. The 465 companies in the S&P 500 Index in January 2019 that were publicly listed between 2009 and 2018 spent $4.3 trillion over that decade on buybacks, equal to 52% of net income, and another $3.3 trillion on dividends, an additional 39% of net income.

In 2018 alone, even with after-tax profits at record levels because of the Republican tax cuts, buybacks by S&P 500 companies reached an astounding 68% of net income”

https://hbr.org/2020/01/why-stock-buybacks-are-dangerous-for-the-economy

“The restaurant industry spent 140 percent of its profits on buybacks from 2015 to 2017, mean. The retail industry spent nearly 80 percent of its profits on buybacks, and food-manufacturing firms nearly 60 percent. All in all, public companies across the American economy spent roughly three-fifths of their profits on buybacks in the years studied. “The amount corporations are spending on buybacks is staggering,” Milani said. “Then, to look a little deeper and see how this could impact workers in terms of compensation, was staggering…..”

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2018/07/are-stock-buybacks-starving-the-economy/566387/

There are several factors behind this drive to financial exploitation of the corporate surplus: the tendency of rates of profit to fall, diminishing opportunities, financial de-regulation, globalisation has made the extraction of surplus value from labour in the developing world much easier etc etc

However, the process began with the advent of the neoliberal era in the early 1980s and the fall in the taxation rates on the wealthy, along with the scrapping of exchange controls and other financial deregulation in the UK that helped turn the City of London into the global hub of international tax avoidance. This coincided with concerted attacks on the trade union movements that further enabled the ruling classes to increase their share of the cake.

There are problems inherent in the basic capitalist imperative of accumulation, those problems are clearly exacerbated by income inequalities and tax regimes that allow the wealthy to arrogate even more of the economic surplus and utilize it for activities that range from non-productive to dangerous.