Lessons learnt from practical application

Read the part 1 and part 2 of this article.

Stalin

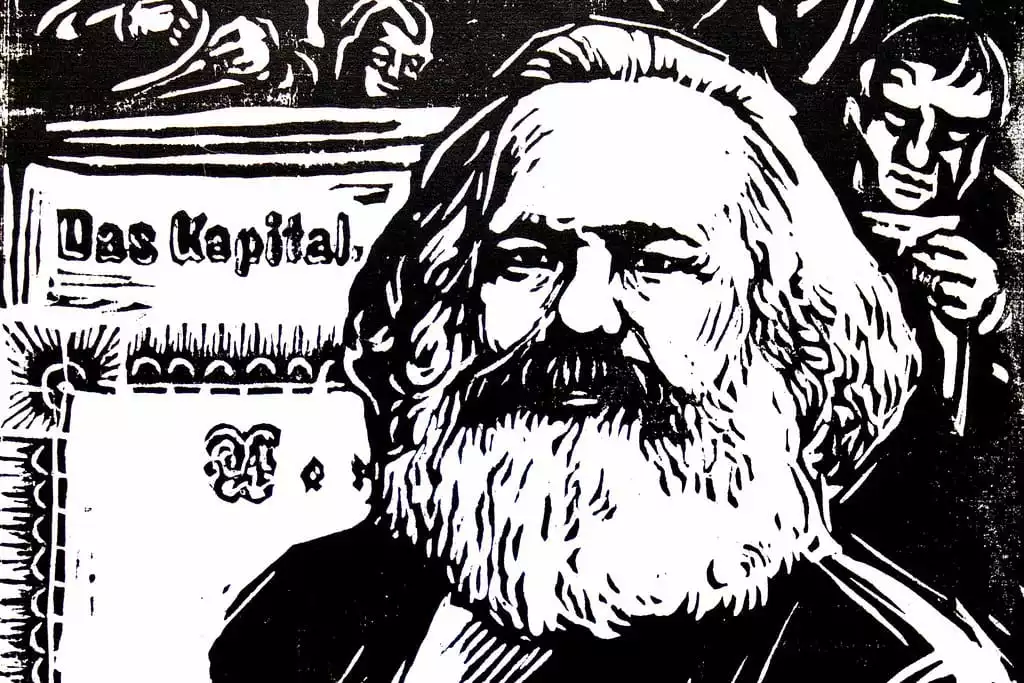

Let us turn now briefly to consider a text written almost a hundred years after the Communist Manifesto first appeared: Josef Stalin’s Dialectical and Historical Materialism of 1938 is a text that attempts to summarize and synthesize the essential theoretical insights of Marx and Engels with the historical experience of the Russian Revolution and Vladimir Lenin’s theoretical contributions. As with all of Stalin’s writing, we find a very simple and straightforward look into the most important features of this theoretical and practical inheritance, written from the standpoint of a successful revolutionary state attempting to construct socialism amid all the pressures and difficulties of war and economic competition with the Western imperialist alliance. So what is it that Stalin believes most essential to understand regarding dialectical and historical materialism? “In its essence, dialectics is the direct opposite of metaphysics.” With Marx, he tells us, the dialectic becomes fully material. For the dialectical materialist, it is not simply that things stand before ideas, but that all ideas are developments of a world of matter, that is, relations of forces that develop objectively, which includes our subjectivity and ideas about the world. Ideas do not bind the world as in Plato, Kant, and Hegel; ideas are bound by the world, by a development of forces that include ideas within a dialectic of inside and outside, subject and object, form and forming. Marx and Engels developed the theoretical position of dialectical materialism, ultimately anchoring it within historical materialism, which is that position of critique and analysis that analyzes the development of the human world, its social, economic and political relations dialectically. The analysis of the capitalist form within Marx’s defining work Capital is the sustained and exhaustive, though by no means complete, contribution to a historical materialist understanding of the modern world. Stalin synthesizes four features of the Marxian philosophical materialism:

1. Nature connected and determined – interpenetration of all things, inseparable from all other things.

2. Nature is determined by continuous movement and change – phenomena are essentially change. All nature, from the smallest and largest, ceaselessly come into and out of being.

3. Quantitative change leads to qualitative changes – leap from one state to another – process of development is an onward and upward movement, simple to complex, lower to higher. No eternal return of the same, time is not a closed circle. Phenomena have certain points by which they make a leap from one form to another. The idea that quantitative change leads to qualitative change in fact derives from Hegel. The natural scientific definition of this idea is that of a “phase change.”

4. Internal contradictions internal to all things – positive and negative, coming into being and passing away – internal development of the process of quantitative into qualitative – dialectics the study of the contradictions within things.

Everything depends on the contradictions, the time and place of things, Stalin says. Contradictions reveal the law of development, showing that history is not just a jumble of accidental phenomena. Revolutions are the development of quantitative into qualitative change, the movement of contradiction within society. All great changes in human history have been brought into existence through revolution, through the negation and overturning of one form and development of another. For Stalin, the laws of development of society are in principle fully knowable: the science of the development of society can become a hard science. Socialism is a science, the unity of theory and practice. The conditions of ideas, historically considered, must be sought in the material development of societies: social being determines consciousness. The Party of the proletariat must base its analysis in the material development of society, not in abstract ideas or views. Ideas, however, can and do have influence on the material conditions of society; there need to be ideas developed out of a concrete analysis of these material conditions. As Marx says: ideas become a material force once they grip the masses.

What are the conditions of material life of society? Stalin asks. Nature, geographical environment, size of population, are all important, but not the chief determining forces. The mode of production, rather, is that which forms the most essential conditions of the material life of society. The relations of people within production is internal to the mode of production; all modes of production are social relations between people. Production is always in a state of change and development: theories and institutions are based on the state of development of the productive aspects of society. Changes in development occur through changes in the relations of production and the development of the productive forces. Under socialism, according to Stalin, there is correspondence between the relations of production and the productive forces. The essential comes down to the question of who commands the relations of production and owns the means of production: in capitalism, the very few own the means of production and command the relations of production, whereas in socialism, control is held by the many.

Stalin then gives a very broad overview of the main types of relations of production in history: 1. primitive communal relations of production, ownership in common; 2. slave societies commanded by the slave owner, appearance of division of labor, means of production in few hands, oppression of one class by another; 3. feudal system that allows for some independence of the toiling class, the lord not directly owning the peasant but does own the land, exploitation is still nearly as severe as under slave system; 4. capitalist system concentrates means of production in hands of the few, laborers sell their labor to the capitalists, advent of machinery and need for higher degree of skill among laborers; capitalism has socialized productive forces but keeps private ownership in the hands of the few, leading to irreconcilable contradiction between the social relations of production and the ownership of the means of production; 5. socialism brings social ownership of the means of production, frees the social relations of production from the ownership of a few.

Commenting on this genealogy of historical forms, Stalin emphasizes how the rise of new productive forces necessarily develop from a previous form, thus, people cannot choose what productive forces they want. But revolutions in production give rise to effects that cannot be predicted: people enter into relations that are independent of their will and out of new relations of production there are birthed new ideas that then in turn bring about new productive forces that lead to new revolutions in the relations of production.

We can thus see throughout this text how Stalin attempts to simplify the language and condense the main points of what had been arrived at nearly a century earlier. Yet what is added is the experiential content of a revolutionary society attempting to construct that historical break and new stage of history that Marx and Engels envisioned. That this did not ultimately succeed should not prove that the principles were incorrect: ultimately the contingent developments of history impose upon the construction of socialism where it has come to state power a field of struggle that cannot be known in advance, and which brings unforeseen difficulties and pressures that can and have led to the destruction of socialist state experiments. That an experiment fails, however, should not lead to abandoning the science: the science needs to be adjusted to account for these failures, whether they arise internally from errors in the application (or abandonment) of principles, or are imposed externally by the pressures and difficulties of struggle with the alliance of bourgeois states. Stalin helps to teach us, both in his errors and successes, how to approach historical materialism as a science, that is, as something that does not exist merely in theory but in its practical application.

Mao

Just a year before the publication of Stalin’s Dialectical and Historical Materialism in 1938 appeared two texts written by Mao Zedong, On Practice and On Contradiction, essays comprised of lectures given nearly a decade before the consolidation of what would become the People’s Republic of China. We will not here go into every detail of these texts, but the underlying philosophical analyses of Mao both continue the lineage of dialectical and historical materialism inaugurated by Marx and Engels and offer some additions and elaborations that are worth considering. Mao presents his texts as a critique both of idealist dogmatism and mechanical materialism—that is, undialectical materialism or empiricism—through the articulation of the universality and particularity of contradiction, the affirmation of the fundamental relatedness of all things, and the analysis of the conditions for qualitative change and rupture in history. Mao states that contradiction is not a merely external state of being between separate, self-contained entities, but inheres internally in the essence of all things: things are self-contradictory, containing opposing principles, which is the reason for all development and change in nature and society. At this level, Mao is fully Hegelian in this conception, who as well understood contradiction as internal and all things as containing their opposites. When it comes to human society, Mao understands this self-contradictoriness expressed as what Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin had already understood as the fundamental contradiction between the productive forces and the social relations thereof: “Changes in society are due chiefly to the development of the internal contradictions in society, that is, the contradiction between the productive forces and the relations of production, the contradiction between classes and the contradiction between the old and the new; it is the development of these contradictions that pushes society forward and gives the impetus for the supersession of the old society by the new” (70). This contradiction between the forces of production and the forms of ownership will thus be understood as the principal and fundamental contradiction, that which is most determinative of the general movement of society whose resolution will bring about a new historical epoch. This new epoch arrived at through the resolution of the old contradiction does not mean that contradiction has been eliminated: since Mao understands contradiction as the essence of all things, the unity of opposites as the fundamental law of the universe’s unfolding, there will arise new contradictions in this new stage of development. The aim of the new socialist society, however, is to replace antagonistic contradictions with non-antagonistic ones, which is to say, move beyond the destruction and violence that accompanies antagonistic contradictions within class society. “What is meant by the emergence of a new process? The old unity with its constituent opposites yields to a new unity with its constituent opposites, whereupon a new process emerges to replace the old. The old process ends and the new one begins. The new process contains new contradictions and begins its own history of the development of contradictions” (75). Mao then stresses that a proper understanding of these processes cannot come about without observing the difference between the universality and particularity of contradiction. Mao upholds an essentially Newtonian orientation toward the proper process of rational cognition when he affirms that our knowledge moves from the observation of particular contradictions in particular things to the discovery of universal contradictions expressed as general laws of development, and then from those laws back to the particularity of things, which have become enriched and expanded through the discovery of universals. “These are the two processes of cognition: one, from the particular to the general, and the other, from the general to the particular. Thus cognition always moves in cycles and (so long as scientific method is strictly adhered to) each cycle advances human knowledge a step higher and so makes it more and more profound” (77). Mao is here essentially restating the general form of modern scientific method, which he opposes to one of the main objects of critique in these essays: philosophical dogmatism, largely Hegelian-inspired, though in a way much less sophisticated than Hegel aimed at discovering universal laws from reason alone and applying them to a wide variety of particular forms of contradiction. “Our dogmatists are lazybones. They refuse to undertake any painstaking study of concrete things, they regard general truths as emerging out of the void, they turn them into purely abstract unfathomable formulae, and thereby completely deny and reverse the normal sequence by which man comes to know truth” (77).

We are thus presented with a difference between particular and universal contradictions, a distinction that was already philosophically developed by Hegel and presupposed by modern scientific method. But what I would most like to emphasize here is the importance and main critical contribution of Mao to the theoretical development of historical materialism in this text, which happens through the understanding and generalization of qualitatively different contradictions whose resolution require qualitatively different methods. Marx, Engels, Lenin and others had already understood and put into practice the qualitative differences between contradictions and the need to develop different method of resolving them, thus, that class struggle, fundamental as it may be, is one form of contradiction but that other forms of contradiction exist within society that require different forms of organization and struggle to overcome. Mao, and then Deng Xiaoping after him, each in their different ways pushed this conception forward and gave it an emphasis and elaboration that marked the specificity of socialism with Chinese characteristics, and I would argue, is one of the reasons the Communist Party of China and the People’s Republic has survived up to now. Mao thus writes: “Qualitatively different contradictions can only be resolved by qualitatively different methods. For instance, the contradiction between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie is resolved by the method of socialist revolution; the contradiction between the great masses of the people and the feudal system is resolved by the method of democratic revolution; the contradiction between the colonies and imperialism is resolved by the method of national revolutionary war; the contradiction between the working class and the peasant class in socialist society is resolved by the method of collectivization and mechanization in agriculture; contradiction within the Communist Party is resolved by the method of criticism and self-criticism; the contradiction between society and nature is resolved by the method of developing the productive forces. Processes change, old processes and old contradictions disappear, new processes and new contradictions emerge, and the methods of resolving contradictions differ accordingly” (78). This understanding of the many contradictions beyond or in addition to those of class gives the historical and dialectical method a greater fluidity and concreteness, and thus a greater imperviousness to dogmatism and rigidity. There were of course errors and transgressions committed by the Communist Party of China under Mao that we would not want to repeat which were the results, we might say, of precisely those forms of dogmatism that Mao critiques in these texts. But in the theoretical articulations Mao provides here, there is much to take away. In fact, a close reading of Mao and theoretical engagement with his thought is the best way to refute precisely that dogmatic idealism he denounced that is today expressed by many self-proclaimed Maoists, who dogmatically appropriate certain concepts and phases of development in China and attempt to make general principles universally applicable to particular situations much different than those that existed in China at the time. The best critique of so-called Maoism is found within On Contradiction, when Mao states: “The principle of using different methods to resolve different contradictions is one which Marxist-Leninists must strictly observe. The dogmatists do not observe this principle; they do not understand that conditions differ in different kinds of revolution and so do not understand that different methods should be used to resolve different contradictions; on the contrary, they invariably adopt what they imagine to be an unalterable formula and arbitrarily apply it everywhere, which only causes setbacks to the revolution or makes a sorry mess of what was originally well done” (78).

Historical Materialism Today: CPUSA

In an article published in December 2020 entitled “Let’s bring back the “plus.” Here’s why”, Communist Party co-chair Joe Sims elaborates an understanding of the role of the communist movement as that which both in theory and practice adds to each struggle of people against oppression a unifying element, articulating a fundamental interrelatedness, a dialectical interpenetration, of all these forms of struggle. This is the “plus” aspect of communism: it interweaves what appear as separate or distinct, showing their fundamental interrelations as manifestations or particular contradictions that are qualitatively different and thus require qualitatively different methods of resolution: the struggle against patriarchal domination, against white nationalism and structural racism, against gender and sexual bigotry, against democratic and electoral restrictions, against environmental degradation, against the continued erosion of Native-American autonomy, against wars of aggression and imperialism, and of course, against workplace and economic oppression are all different forms of contradiction that require different forms of resolution. Different contradictions and forms of resolution however do not negate but in fact logically imply a universal and principal contradiction, which is precisely that contradiction articulated by Marx and Engels up to Mao: that between the productive forces and the social relations and form of ownership in capitalism. In other words, communists understand capital as the principal and fundamental contradiction which structures and influences all the other contradictions that exist in society. Joe writes: “Fighting for reforms is an essential feature of the battle against capitalism. However, without the conscious, purposeful activity of a revolutionary working-class party, this essential work is likely to remain in the arena of reforms, that is, it will not touch the power of capital.” Although comrade Sims did not phrase things in quite this way, Mao’s conceptual vocabulary of particular and general contradictions, principal and non-principal contradictions, and the qualitative differences between contradictions is a powerful way of understanding the communist “plus” he articulates: this “plus” is in fact the power of dialectical movement as it expresses itself in reality and in our understanding of this reality: it is the historically specific, determinate interaction of forces and the conscious engagement with them, developing the movement of particular contradictions and the particular modes of resolving them in view of the general forms of contradiction that unite them, all oriented toward the overturning of the principal, antagonistic contradiction still binding us, that between the productive forces and the capitalist form of ownership of those forces that defines the capitalist epoch. As we learn from Mao, though, resolving the principal contradiction will not of itself resolve the other contradictions, but it will transform the general terrain on which their dialectical movement plays out, hopefully in a way that is less antagonistic than that which exists within capitalism.

The communist plus can of course also be dialectically understood as the communist minus: as that which, to use a well-used phrase, negates the negation inherent in supposedly separate, isolated things, bringing them together in a unity to smash the principal negation of capitalism, that of private property in which a few own everything and the many own little to nothing, what Marx and Engels trenchantly express in the Communist Manifesto as follows: “You are horrified at our intending to do away with private property. But in your existing society, private property is already done away with for nine-tenths of the population; its existence for the few is solely due to its non-existence in the hands of those nine-tenths. You reproach us, therefore, with intending to do away with a form of property, the necessary condition for whose existence is the non-existence of any property for the immense majority of society” (56). This theoretical understanding of the principal and fundamental contradiction is the “plus”—or the “negative” depending on how one views it—that communists bring to all the struggles we are engaged in. The Communist Party USA, from William Foster to Elizabeth Gurley Flynn to Henry Winston to William Patterson to Claudia Jones to Gus Hall to Joe Sims and Rosanna Cambron and all of us today work within this space of historical materialism, within the particularity and generality of the contradictions of capitalist society in view of moving definitively out of it and into a new historical epoch.

Works Cited:

Engels, Friedrich. Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. Paris: Foreign Languages Press, 2020.

Marx, Karl & Engels, Friedrich. The Communist Manifesto. London: Pluto Press, 2008.

Sims, Joe. “Let’s Bring Back the “Plus.” Here’s Why.” https://www.cpusa.org/article/lets-bring-back-the-marxist-plus-heres-why/, 2020.

Stalin, Josef. Historical and Dialectical Materialism. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1938/09.htm

Zedong, Mao. On Practice and Contradiction. London: Verso, 2007.

Editor's Note:

The views and informations expressed in the article are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect the views of The International. We believe in providing a platform for a range of viewpoints from the left.