Development of modern principles of dialectical and historical materialism

Read the part 1 of this article.

Kant

Without Kant (born 1724 in Konigsberg, East Prussia; died 1804 in Konigsberg) there would be no Hegel, and consequently no Marx or Engels. Kant, we can say, stands at the beginning of our modernity, through which a fully modern philosophical outlook is first brought into being. What is the meaning of Kant’s so-called “Copernican Revolution” in the world of thought? With the publication of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason in 1781—which, with the Critique of Practical Reason (1788) and Critique of Judgment (1790) form the three-part articulation of his critical philosophical system—we have the emergence of what is referred to as the subjective turn in philosophy. Rather than a doctrine or system that works out a positive knowledge of the world as it is in itself, which is what philosophy since Plato and Aristotle had hitherto concerned itself with as a form of knowledge co-terminus with natural science, Kant introduces a radical reduction of all philosophical pretensions of positive knowledge of the objective reality of things to the sphere of subjective conditions of appearance. In other words, for Kant, we cannot know how things exist in themselves independently of our subjective intuitions and concepts of them; our knowledge of the world, then, will always be the knowledge of how we subjectively construct that world. Of course, we can immediately feel the familiarity of this orientation, of this subjective turn, in all its modern and post-modern variations. But for Kant, this did not mean that our knowledge was wholly contingent and subjectively relative: quite the contrary. Kant installed the conditions of objective knowledge fully within the subject, giving subjectivity the primacy of place in the discovery of objective laws whether in nature or in the world of morals. In this way, Kant gives to the subject the universality and freedom that from Plato onward had largely existed in the subject’s immersion in a supposedly objective realm of ideas or things. The subject is now fully free to discover its own laws, which are not contingent but universally given to the subject as the very forms of its experience and knowledge. Kant’s First Critique, which treats of knowledge, the Second Critique, which treats of morality, and his Third Critique, which treats of beauty, are thus together a rewriting of the conditions of truth, morality, and aesthetics that subtracts or negates the origin of these terms as belonging in things. And yet, this radical rupture introduced between subject and object was understood by Kant not to lead to a permanent separation of the world of concepts and the world of things, but to their fullest integration: the critical philosophy of Kant had the chief task of critiquing the illusions of reason and its pretensions to discovering the truth of objects. For Kant, there can be no ultimate truth discovered in objects, but only an infinite movement toward the thing as it is in itself, which is ultimately unknowable in itself. In this way, Kant replaces philosophy as a positive doctrine with philosophy as a negative movement of critiquing the conditions of knowledge and limiting the overstepping of reason with respect to the natural sciences, which with Newton’s scientific revolution had established an objective footing that uprooted the previous proximity of natural science and philosophy. This critique of illusions of reason that Kant put forward primarily in the Critique of Pure Reason was articulated not simply as a set doctrine and unity of principles for the discovery of truth, but as the dialectical movement of reason’s encounter of itself, which implicitly contains the entire history of philosophy and knowledge that are the general conditions of the emergence of Kant’s critique. Thus, while the transcendental idealism that he elaborates has in common with Plato’s idealism a certain approach toward the infinite as a teleological beyond in the endless pursuit of which the thinker is engaged as well as a position of doubt and critique of illusion, Kant’s philosophy innovates an internal dialectical approach that foregrounds what we can call the historical determination of knowledge, with dialectics being the working out of the historical process of reason’s coming to know itself. Thus, while Kant is certainly not a historical materialist, he introduces this historical and dialectical movement of ideas, a movement that Hegel will take up and push beyond the self-imposed limitations of Kantian transcendental idealism. Let us turn then to an analysis of Hegel’s absolute idealism, with a specific look at how Hegel inscribes history within the movement of ideas, which will be determinative for the development of the historical materialism of Marx and Engels.

Hegel

Like Kant, Hegel (born 1770 in Stuttgart, died 1831 in Berlin) understood the objective reality of knowledge as a historical process, moving from lower to higher forms. Yet for Hegel, the lower forms are not simply cancelled out or dialectically refuted and jettisoned like they are for Kant, but rather they are aufgehoben, that is to say “sublated,” contained in a new form in a higher stage of development. The common characterization of Hegel’s dialectics as the movement of thesis-antithesis-synthesis is thus misleading and nowhere articulated as such in Hegel’s writings. It is misleading because it creates a conception of external, self-contained entities that meld into each other, leaving nothing behind. Rather, Hegel’s entire philosophy is mobilized to overcome the idea of substantial externality: the dialectical movement of the idea is the self-realization of the fundamental interconnectedness of all things, that is, an absolute and unified reality. Thus it is not so much a movement of synthesis as one of overcoming the conceptual isolation of things from one another and the alienation of subject from object, which for Kant was inscribed at the very center of his philosophical project. The Hegelian dialectic is the historical unfolding of the Idea, an unfolding whose motive force is contained within the Idea. The material world is the form of appearance of the Idea such that it thus contains materiality within itself. For Marx/Engels, this dialectical movement is reversed: materiality contains ideas within itself. Historical unfolding is that of the co-determination of ideas and material things, with materiality acting as the a priori condition of ideational development. This does not mean that Marx/Engels negate the formative influence of ideas on material reality, but rather that ideas do not pre-exist material reality or act independently on it. Yet for both Hegel and Marx/Engels, there is no thinking outside of history. The movement of truth is inseparable from the movement of history: “philosophy is its own time captured in thought.” History is not just a collection of contingencies; there is no knowledge without general laws of development. However, these general laws cannot produce an inductive knowledge of what will result in history. Historical understanding is retrospective: that which emerges cannot be fully predicted from what comes before. Only in retrospect can that which comes into existence be seen as necessary, changing the past itself insofar as it is something known. Hegel understands each stage of historical unfolding as equally necessary to the essence of a thing. The cancelling through sublation and inclusion of the negated elements form the totality of what gives a thing its essence. Unlike Kant’s transcendental idealism, Hegel’s was an absolute idealism, acknowledging a single and absolute reality of which the concept is both subjectively for us and objectively in itself. This independent reality is defined by becoming, ceaselessly in movement, which is the dialectic of being and nothingness, the coming into and out of existence. This movement is driven by nothing exterior to it; change and becoming are identical to the absolute reality itself. We can thus see throughout Hegel’s philosophy the influence of Heraclitus, of whom Hegel spoke reverentially with the claim that Heraclitus had already comprehended the essence of what Hegel set about to complete in a systematic way. We should thus approach Hegel in a way that befits the complexity of his thought, rather than reduce his thinking to simplistic formulas or to an abstract conception of idealism that doesn’t correspond to the nuances of treatment Hegel gives in his interpretation of material reality. We do not need to make of Hegel a bogeyman, despite what can certainly be criticized regarding his acquiescence to the constitutional monarchical order of his time and his racist beliefs in the edifying and spiritual benefices of European colonization. Marx clearly valued Hegel highly enough as a thinker to assimilate many of the dialectical maneuvers Hegel develops into his own analysis of capitalism. Hegel is thus a highly contradictory figure and should be approached as such. But let us move now to how Marx and Engels move beyond Hegel and the philosophical lineage leading up to him.

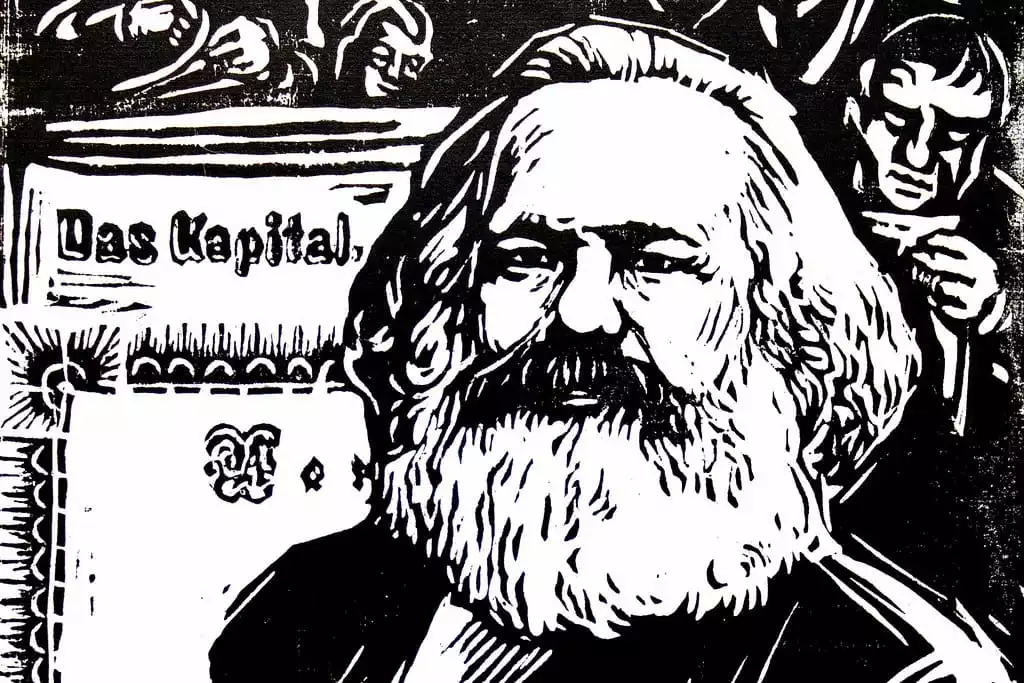

Marx/Engels

With Marx and Engels, a systematic approach of dialectical thinking is given shape in a way that revolutionizes the history of metaphysics up through Hegel. If with Hegel we find emerge a subjectivity whose truth is the history of its ideational forms continually sublating prior forms, rising with each stage to a higher, more absolute and universal consciousness wherein the divisions between thought and thing, subject and object, progressively melt away in the univocity and oneness of being—the Heraclitan-inspired Absolute—then we can say that what Marx and Engels introduce to this dialectical movement is precisely that thing which Hegel believes to have captured and transcended within the realm of ideas: materiality and finitude, an externality that cannot be mediated through concepts alone. They redevelop dialectics along the lines of a practice that is not reducible to the concept’s self-movement within the historical forms it occupies: practice here involves a collective subject, but one which goes beyond the phenomenal forms of collective subjectivity Hegel describes in Phenomenology of Spirit and the form of the perfect rational and free modern state he imagines in his Philosophy of Right. Marx and Engels evince a subjectivity that is comprised in the great majority of individuals who have been systematically excluded from the full possession of rights within the historical form of developing capitalist society. It is this subjectivity—the proletariat, the working class, the great majority whose labor is the engine of the productive and reproductive movement of society—that is the true bearer of dialectical movement as it concerns human society and inter-subjective life. The abstract, dialectical form taken as a method of reflective interpretation and analysis, whether this is materialist or idealist in orientation, becomes in Marx and Engels that which arises from the labor of collective humanity in its relation to that part of it which preside over and appropriate the objects of this process. Class struggle, the movement of humanity in conflict with itself, becomes the determinative form of actually existing dialectical phenomena as it concerns human reality: dialectics become fully material and historical insofar as it is understood as that which expresses the contradictions of society at each stage of development. The ideas produced within society are to be traced back to the historical forms of their appearance: there is an historical a priori that reverses the direction of explanation provided by Kant and extended throughout European Enlightenment philosophy. What is here materialist and moves against idealism is this treatment of material things and processes as having precedence to the reflective ideas we form about them. For Kant and Hegel, there was on the contrary the desire to prove how each and every material perception we have is thoroughly mediated by concepts that are universally given to consciousness as the seat of reason and freedom. With Marx and Engels, however, the material forms come before consciousness and conceptual inventories as the conditions of their emergence: thoughts, we could say, are forms by which material reality expresses itself, and in this sense Marx and Engels are closer to the monism of Spinoza than they are to the transcendental or absolute idealism of Kant or Hegel.

Historical materialism is then the method of understanding the emergence of collective forms of organization of human society and all that is contained within it through an analysis, not of the logic of its conceptual forms with respect to a transcendental or spiritual notion that teleologically informs it, but rather through the material processes that in each epoch shape the general forms of human interactivity and their corresponding concepts. This method, as we have stated, is not simply an affair of the philosopher, but is the vehicle by which a class subject becomes conscious of itself so as to transform the material and conceptual conditions within which it finds itself, an orientation summed up in Marx’s celebrated 11th Thesis on Feuerbach according to which “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it.” For historical materialism, the method of analysis is tied to the practical activity of a collective subject as the theoretical vehicle by which this subject revolutionizes the conditions of its material being so as to do away with that aspect of domination and subordination that has characterized the majority of human history leading up to the emergence of capitalism. Historical materialism is thus a way of rooting oneself in the conditions of the present in such a way that the material history of that present becomes known in view of a fundamental rupture that will bring about a new future. Such a rooting, however, is done not merely according to a utopian ideal of development but rather in accordance with a scientific approach to the material of experience. “Science” here is more than the commonplace view of a disinterested pursuit of truth through the rigorous application of concepts: what Marx and Engels have in mind is the science of liberation, which is to say, a supremely interested, rational approach toward achieving liberation of oppressed peoples and sublating the capitalist form through the development of socialism. Historical materialism is the method of scientific socialism, its theoretical motor and, as activity of its collective subject, the practical application of its findings and logical consequences. Let us now look at what Marx and Engels themselves say concerning this science which they helped bring into being.

In his Socialism: Scientific and Utopian, Engels treats of the Hegelian dialectic, describing the contradictions that animate it which do not resolve into scientific method but rather keep its systematic nature suspended above the world of things, straining toward an absolute reason that even by its own logic can never be achieved: “On the one hand, its essential postulate was the conception that human history is a process of development, which, by its very nature, cannot find its intellectual final term in the discovery of any so-called absolute truth. But on the other hand, it laid claim to being the very essence of precisely this absolute truth. A system of natural and historical knowledge which is all-embracing and final for all time is in contradiction with the fundamental laws of dialectical thinking; which by no means excludes, but on the contrary includes, the idea that systematic knowledge of the entire external world can make giant strides from generation to generation” (60). Thus, the attempted closure that Hegel’s system lays claim to, contradicts what Engel’s understands as the endless movement of revolutionary progress whereby leaps in the objects and form of knowledge have been and will continue to be made. The science of totality with which Hegel and other Enlightenment philosophers were engaged had become with the advent of modern science sublated by the logic of the sciences themselves: “modern materialism is essentially dialectical and no longer needs any philosophy standing above the other sciences. As soon as each separate science is required to clarify its position in the great totality of things and of our knowledge of things, a special science dealing with this totality is superfluous” (60-61). In what position, then, does that put the scientific socialism of Marx and Engels? Is there not within the logic of historical materialism a certain totalizing conceptual dimension that resolves the various aspects of human society and practices, science included, to a common denominator of class struggle? We affirm that there is a determinate totality envisioned through scientific socialism, but that this totality is not a logically subordinating structure or totalizing idea of spirit or moral cohesion, but rather the scientific analysis of the forms of production of society, namely capitalist society, which itself claims in theory and practice the status of being universal. Marx and Engels’ historical materialism is thus the rigorous critique of the bourgeois concept of universality that had emerged as the totalizing frame of reference for understanding the entire historical development of the human species. In his critique of the idealist conception of history, Engels writes: “the old idealist conception of history…knew nothing of class struggles based on material interests, indeed knew nothing at all of material interests; production and all economic relations appeared in it only as incidental, subordinate elements in the “history of civilization”” (61), adding that “Hegel had freed the conception of history from metaphysics—he had made it dialectical; but his conception of history was essentially idealistic” (62). In opposition to the idealist conception of history, metaphysical or otherwise, Engels asserts the worldview developed by himself and Marx as the materialist and dialectical approach to seizing theoretically and practically the essence of historical movement, which does not begin with abstracted ideas and personages such as one finds in “histories of civilization”, but rather with the forms of material production and reproduction put in motion by human labor structured according to divisions of ownership and dispossession, command and subordination, domination and exploitation: in a word, class difference: “The materialist conception of history starts from the principle that production and, next to production, the exchange of things produced, is the basis of every social order; that in every society that has appeared in history, the distribution of wealth and with it the division of society into classes or estates are dependent upon what is produced, how it is produced, and how the products are exchanged. Accordingly, the ultimate causes of all social changes and political revolutions are to be sought, not in men’s brains, not in their growing insight into eternal truth and justice, but in changes in the modes of production and exchange” (65). These “changes in the modes of production and exchange” contain the secret of how historical progress is not just to be interpreted but put into action, that is, consciously made into an object of revolutionary activity. The entire stretch of Marx and Engels’ writings and the scientific nature they claim revolves around the meticulous study and practical uptake of the dialectical movement expressed as contradiction between the material as well as ideological forms of production and the social relations that these forms bring about. The essential insight is that capitalism has revolutionized on a scale hitherto unknown in human history the forces of production and in so doing has brought about new forms of social relations that already in Marx and Engels’ time had superseded the capitalist class divisions and relations of ownership that these divisions imply. The capitalist form of production has socialized humanity, collectivized the great majority of the population into a working class, the proletariat, who forms the material basis and source of value created by the capitalist form. Yet this great majority, rather than appropriating the full value of what their labor produces, has been forced to sell themselves as value creators to capitalists, a tiny minority that lives by sucking this vital energy and turning it into profit. The problem is thus not developing a socialist utopia wholly outside and independent of capitalism, but of pushing forward the socializing forms of relation that capitalism has itself brought about to a higher form and thereby sublating capitalism, resolving the contradiction between the forms of production and the modes of social relation which have kept the great masses of humanity in a state of deprivation and alienation from what they themselves have brough into existence. Engels writes: “The new productive forces have already outgrown the bourgeois form of using them; and this conflict between productive forces and mode of production is not a conflict engendered in men’s heads, like that between original sin and divine justice, but it exists in the facts, objectively, outside us, independently of the will and even actions of the men who have brought it on. Modern socialism is nothing but the reflex in thought of this actual conflict, its ideal reflection in the minds above all of the class directly suffering under it, the working class” (66).

The proletariat, the vast masses of humanity who are driven to sell their labor through an unequal relation to the capitalist who exploits this inequality to his vast gain, is that historical force which is the living embodiment of dialectical movement insofar as it is through the labor of this class that the historical form of capitalism has come into existence, and it is through this class that capitalism will pass away: it is not simply negated by that which is already formed as its opposite (thus, not according to the formula of thesis-antithesis-synthesis), but through its self-negation will it be transformed into something qualitatively new. The proletariat does not stand outside of history, thus not outside of capitalism: the vast working class passes through the capitalist form, which thereby makes proletarians, that is, wage-earners of all kinds, the force of negation internal to capitalism, its self-overturning into socialism. It is in this way that in the Communist Manifesto Marx and Engels simultaneously describe and summon this vast collective subject: “All previous historical movements were movements of minorities, or in the interest of minorities. The proletarian movement is the self-conscious, independent movement of the immense majority, in the interest of the immense majority. The proletariat, the lowest stratum of our present society, cannot stir, cannot raise itself up, without the whole superincumbent strata of official society being sprung into the air” (50). This is a subjectivity, they stress, that has been brought into existence by the bourgeoisie; what had previously been relatively isolated more or less self-sufficient communities of laborers spread throughout the town and countryside had become with the advent of modern industry a vast collectivized working body. Such a collective body will have superseded the relations of production for which it was initially constructed: “The development of modern industry [ ] cuts from under its feet the very foundation on which the bourgeoisie produces and appropriates products. What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own gravediggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable” (52). This new historical materialist method therefore not only redirects at a theoretical level the form and object of analysis of dialectical method but has created a new subject by which this theory and practice are brought into play: the class subject, the vast collective being of real, historically determined human beings engaged in shared struggle for material freedom from want and misery. “The theoretical conclusions of the communists are in no way based on ideas or principles that have been invented, or discovered, by this or that would-be universal reformer. They merely express, in general terms, actual relations springing from an existing class struggle, from a historical movement going on under our very eyes” (53).

Editor's Note:

The views and informations expressed in the article are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect the views of The International. We believe in providing a platform for a range of viewpoints from the left.