Written by comrade McGill around 18months ago but the principles remain current and relevant, the British government are still using misconceptions and lies about the national debt in order to attack the working class.

In 1983 Margaret Thatcher said that “the state has no source of money other than the money people earn themselves. If the state wished to spend more it can only do so by borrowing your savings or taxing you more….There is no such thing as public money, there is only taxpayer money.”

“The Government should do what any good housewife would do if money was short,” Thatcher told her adoption meeting as a Conservative Candidate for Dartford on 28 February 1949. “Look at their accounts and see what was wrong.”

These two statements betray two major misunderstandings: the capacity of sovereign governments that print their own currency to create that currency independent of taxation; the capacity of such governments to run persistent and significant fiscal deficits without damaging the economy, raising interest rates to damaging levels nor endangering the governments’ ability to finance any deficits.

Thatcher probably understood this, her words were designed to connect to middle-class voters who see them as “sensible” arguments, demonstrate her “prudence” and serve as a pretext for her ideological mission to reduce the role of the state in the economy and weaken the welfare state. However, the specious “household fallacy” continues to be exploited by cynical politicians to justify policies that do untold damage to the poorer people in their economies, and mouthed as a shibboleth by many politicians who simply don’t understand reality.

The following provides a briefing in that reality.

Argument 1: a government should handle its finances as if it were a regular household.

Response:A Government is not the same as a household or an individual: if I spend £40,000 a year but make £30,000 per annum I will accumulate debts and interest on those debts that will eventually mean that nobody will be prepared to lend to me anymore, I will be unable to service my existing loans and I will go bust.

Had I the monopoly ability to print the currency in which I borrow, that would enable me topay-off my debts and lenders would be prepared to advance me funds irrespective of how large my debts grew in relation to my income. Couple that with an ability to control short-term interest rates on my debt and I will not run into debt nor interest payment problems.

This is the position that sovereign governments like those of the UK and USA find themselves, printers of fiat money. Fiat money is government-issued currency that is not backed by a physical commodity, such as gold or silver, but rather by the government that issued it. Governments that do not print their own currency or are committed to keeping their currency at a certain level in relation to other currencies do not have such autonomy regarding the levels of deficit that they can incur nor how much money they can print.

Alan Greenspan, former Chair of the Federal Reserve and a right-wing Ayn Rand groupie, acknowledged this in 2005 when asked a leading question by Paul Ryan at a Congressional hearing on the sustainability of America’s social security system. Ryan wanted Greenspan to say that the government could not afford to foot the rising bill through taxes and that moving to system of private, Wall Street managed accounts would solve the problem. Greenspan, under oath, did not play ball and dismissed the entire premise of Ryan’s question:

“I wouldn’t say that the….benefits are insecure in the sense that there’s nothing to prevent the Federal government from creating as much money as it wants and paying it to somebody.”

All congress had to do was commit to funding the programme and the money would always be there either through “printing money” i.e. electronically creating the dollar balances in the appropriate accounts or borrowing it. The myth that the government had to raise the money through taxation was shot by a right-winger.

But some politicians genuinely do not get it and talk as if the government were a household. In 2010 some American politicians were urging their government to cut the deficit or risk a Greek-style debt crisis. Investors like Warren Buffet knew better, Buffet said: “the US cannot have a debt crisis of any kind as long as we keep issuing our notes in our own currency….Greece lost their power to print their own money, if they could print drachmas they would have other problems but they would not have a debt problem.”

There are obviously constraints on the government’s capacity to continually print money, basically the economy’s capacity to absorb and respond to the additional spending without provoking inflation, see Argument 3 below. The significant creation of money by the UK and USA governments in response to the 2008 crisis did not trigger massive inflation as there were no inflationary pressures in their economies.

Why do governments bother with taxation when they could conceivably just print the money they need? Taxes providean important means of economic control, a means of redistribution to avoid the accumulation of excessive wealth and the resultant political power (the consequences of ignoring this element of taxation are now very apparent),a means of incentivising certain behaviours such as reducing the levels of smoking and drinking and of course as a means of ensuring a demand for the currency that the government prints, if you have to pay taxes in that currency you need to earn some of it.

Argument 2: Continuous “excessive” deficits will mean we will have to pay higher interest rates or nobody will want to finance us and we will need to beg for help, look what happened to Greece.

Response:In 2010 Greece experienced collapsing tax revenues with heavy budgetary obligations and its budget deficit rose to 15% of GDP. To cover this deficit the Greeks had to borrow, but they really did have to “find the money” because they had no Greek Central bank able to issue Drachmas any more.

Lenders were not willing to buy Greek government bonds denominated in euros unless they received a substantial premium for the risk they were in taking in lending billions to a currency user, not issuer, that might not be able to raise the funds in future to pay it back.

From 2009 to 2012 the interest rate on 10-year Greek government bonds rose from less than 6% to over 35%.

Compare that with that with the USA and UK experience:

fiscal deficits in both countries tripled from 2007 to 2009 as a result of the crash.

deficits went from around 3% to 10% of GDP in both countries;

over the same period the average interest rates on ten-year government bonds fell from 3.3% to 1.8% in the USA and from 5% to 3.6% in the UK.

Both countries have the backstop of a central bank that acts for the government as a monopoly supplier of the currency. This reassures investors that bills can be paid and that the central bank has ironclad control over its short-term interest rates and substantial influence over rates on longer-dated securities.

If you’re thinking this all betrays the basic lie at the heart of Austerity, that the only thing that mattered was to cut the deficit or the country would go bust: you are 100% correct.

Why do governments persist with borrowing money from the private sector through issuing bonds rather than just print the money? Again it’s a means of control. The Clinton Government recorded a couple of surpluses in 1998 and 1999. The response was telling: after an initial sense of exultation about the prospect of paying off government debt in total Clinton’s people realised that there would be real issues with wiping out the market for US Treasury Bills: Treasuries are an important safe investment and they were the main instrument for managing short-term interest rates.

(When the Fed wanted to raise interest rates, it sold some of its Treasuries; buyers paid for those bonds using a portion of their bank reserves. By removing enough reserves the Fed could move interest rates up. To cut rates the Fed would do the opposite, buying treasuries with newly created reserves. Without Treasuries the Fed would need to buy other assets and it would look as if were picking winners and losers.)

In addition, buying back its own securities through programmes such as Quantitative Easing (QE) allows the government scope to achieve some policy goals: QE was basically about increasing the price of government securities, as the level of interest on these securities was set at a fixed amount this made the level of return on the bonds lower, they became attractive as an investment and therefore institutions would become more inclined to seek better returns by financing more productive investment. The success of this strategy is questionably but there is little doubt that QE did provide a means of maintaining bank liquidity after the crash.

Argument 3:All this deficit spending and “printing money” lead us into hyper-inflation territory.

Response:The simple answer is that it depends on the amount of slack in the economy and how that economy responds to any stimulus. The $787 billion fiscal stimulus passed in 2009 by Congress didn’t cause an inflation problem in a country stricken by recession; nor did the Brown stimulus in the UK, both economies were suffering serious slack at the time and the spending was absorbed without inflationary spiral.

(This is very much the case in the Covid – Inflicted economies of the current moment.)

Indeed, in the UK as noted by former Bank of England policy-maker Danny Blanchflower in The New Statesman, the budget stimulus in response to the 2008 crash led to Britain's economy actually growing 3.1% between the autumns of 2009 and 2010. Under the coalition in the year afterwards, it grew 0.3% as they began to pursue Austerity, thereby destroying confidence and took us into recession again.

Contrast this with the American experience: they avoided Austerity and Austerity rhetoric: their economy recovered much more quickly than those of the UK and the eurozone and consequently their annual deficits fell much more quickly.

Argument 4: high deficits mean money flowing out of the economy and are unsustainable.

Response:around 70% of UK government debt is held by domestic investors, so those interest payments stay within the country, there is no outflow of funds.

High Debt-to-GDP ratios aresustainable for sovereign currency countries, Japan has a Debt-to-GDP ratio of 240%, (that ratio has been over 200% since 2009) its civilisation survives nicely and its central bank is able to control short-term and long -term interest rates with success.

The Bank of Japan now holds rough 50% of all Japanese government bonds as a result of its market operations to control interest rates;

the Bank of England owns around 25% of UK gilt-edged securities, US government bodies own 27% of American national debt. A large proportion of the headline debt figures you hear quoted have already been effectively retired.

See this from the FT regarding the alacrity with which overseas investors have continued to buy UK government bonds over the last 10 years, the deficit has clearly not deterred them:

Some Deficit and Debt History

To respond to the sustainability issue and give some context, as well as a brief and illuminating economic history

Britain has only recorded a dozen years of budget surplus since 1945. Despite that the government has not gone bust as you would expect to happen to a household in such a situation and the economy has grown considerably since then.

Also, national debt as a percentage of GDP is at the moment not that high historically, is much lower than it was in 1945and for much of the last 300 years.

And the situation since 1910:

This reduction of the Debt: GDP ratio post-war was not due to the government cutting back on expenditure and recording surpluses:

The reduction was due to economic growth and the impact of inflation in reducing the value of the long-term debt.

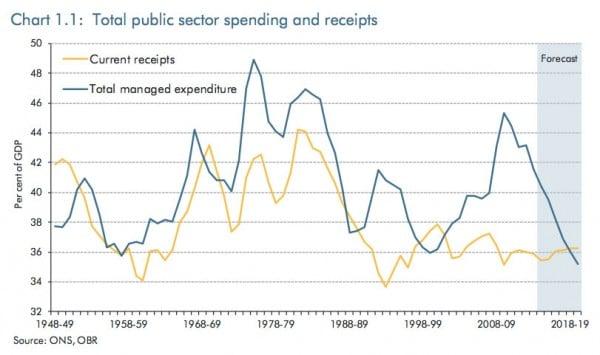

To show further that deficits are compatible with a falling debt/GDP ratio, see the chart below.

From 1971/72 all the way until 1988/89 the UK government never ran a surplus. And yet debt/GDP over the same period fell from 60.0% to 36.6% and real GDP grew significantly, see the chart below.

Check out the growth of UK GDP since 1955. The high levels of public sector debt as a percentage of GDP in the 1950s did not damage the ability of the UK economy to achieve growth, nor did the incurrence of deficits in the middle of the decade reduce growth nor the decline in public sector debt as percentage of GDP. Growth, inflation and keeping real interest rates low are the inter-related factors that contribute to reducing that ratio.

Government deficits will tend to increase when economic activity slows down as the government makes less money from taxation and needs to spend more money on unemployment benefits etc. It also makes sense for the government to make active decisions to increase the deficit to help stimulate economic activity, government deficits contribute to the surplus of the private sector which can have a counter-cyclical effect. If governments seek to balance the books or run a surplus during a downturn then it will be extracting money from the private sector and acting as a pro-cyclical force. Increased deficits are a symptom of downturns, not a cause, as any cursory glance at economic history should advise. Conversely, deficits will tend to fall as percentage of GDP as economic growth expands with all else remaining equal as government receipts rise and welfare commitments fall; again the movement in the deficit is a symptom, not a cause.

The idea that fiscal tightening in order to reduce the size of government deficits would restore investor confidence levels which would in turn promote recovery characterised the European response to the economic downturn/increased public debt following the crash of 2008 and the need to rescue the financial sector. This became known as Austerity, in which reducing the level of public sector deficits became a policy goal in itself irrespective of the short-term hardships it would inflict on weaker members of society.

In late 2018the Institute of International Finance (IIF) has published a series of research papers showing that austerity was a disaster. Fiscal tightening in Europe reduced GDP growth by 10% compared to the US, the IIF says. In terms of GDP growth per capita, the difference was 5%.Trend growth in the US was double that of Europe following the financial crisis, the IIF says, whereas prior to 2008 they had been the same

The main difference between Europe and the US in the post-crisis period was that the US embarked on an era of robust government spending in addition to a massive monetary stimulus package from the US Federal Reserve.

The European Central Bank also adopted a monetary program of low interest rates and quantitative easing (QE). But the European Union continued to enforce its fiscal austerity program, banning member governments from running deficits greater than 3% of GDP. The EU also forced countries to pay down their debts during the recovery. The most dramatic example of that was Greece, which stayed inside the EU's debt repayment program even though its economy shrunk by 45%, peak to trough.

The failure of Austerity is also evinced by Greece’s government debt in relation to GDP: it was 109.4% in 2008, in 2019 it had risen to 176.6%. Contrast that with the experience of the UK in the post war years as more rational economic policies were pursued. Greece has also been damaged by its membership of the euro and its inability to print its own currency, see Argument 2 above.

The IIF paper also points out that the persistent unemployment provoked by Austerity also generates a phenomenon called "hysteresis." It means that when people are out of work for a long time, they lose the skills they need to rejoin the workforce. The economy is then prevented from growing faster when conditions improve because employers cannot find the workers they need, even though there are plenty of people out of work. Austerity inflicts damage on the total economy, over the medium to long terms, it’s more than just a bit of unnecessary short-term pain.

And because interest rates are historically very low, interest payments on the national debt are also currently low in comparison with most years post WW2; certainly lower than most years under Thatcher during which there was no outcry about the sustainability of public debt. The big hike in 2009/2010 was as a result of the debts incurred in order to bail out the financial sector after the crash: the sheer mendacity of the Tory narrative about “spendthrift Labour” is demonstrated by the fact that the Tories pledged to match Gordon Brown’s spending plans for 2007 to 2010.

Argument 5: Government Surpluses are good for the economy

Response: Assume two sectors in the economy, Public and Private.If the government goes into surplus with the Private sector and sustains that surplus it means that the government is taking money from the Private sector.

This means the latter goes into debt; currency users cannot sustain those debts indefinitely in contrast with the currency producer, the government. Eventually they reach the point where it can’t handle the accumulated debt, spending falls lower and the economy falls into recession and possibly depression. Here the government needs to step in, incur some deficits to put the Private sector back into surplus, enable it to pay off some of its debts and start spending again.

Basically, the government is in a much better position to handle sustained debt than the private sector, and if the government does run a sustained surplus then it will be taking money out of the Private sector and increasing its aggregate debt levels.

Real world experience:

Fredrick Thayler of the University of Pittsburgh wrote in 1996, “The USA has experienced six significant economic recessions and each was preceded by a sustained period of budget balancing.”

Since Clayton wrote the Clinton Government recorded a couple of surpluses in 1998 and 1999.

There was a mild recession in 2001 when the stock market bubble that was sustaining consumer spending burst. Mild, but the Clinton surpluses had weakened Private sector balance sheets thereby magnifying the damage caused by the arrival of the Great Recession in 2007.

Argument 6:fiscal deficits require borrowing, everyone competes for a limited supply of available savings, borrowing costs move higher, Private sector projects get ‘crowded out” by the high interest rates and competition for scarce funds from the government leading investment to fall and the economy suffers over the short and longer terms.

Response:“crowding out” is an enduring mantra of the right: it is nonsense theoretically and has no empirical basis.

Go back to our two-sector example, The Public and The Private. If the Govt purchases £100 on new cars from the Private Sector, the Private Sector receives £100. If the Govt taxes the Private sector £100 to finance this spending, then there is no net gain or loss. But if the Govt only taxes the Private sector £90 then there will be a Public deficit of £10 but a Private surplus of £10.

So the private sector will be £10 better off as a result of the deficit and will have more funds available for spending, investment etc. If the government funds the deficit by selling its bonds (Treasuries in the USA, gilt edged securities in the UK) then those bonds are now part of the wealth held by savers in the Private sector so there has been no diminution in the funds available for lending in that Private sector. Government deficits always lead to a pound-for-pound or dollar-for-dollar increase in the supply of net financial assets in the Private sector. Things become a little more complicated when you introduce the overseas sector to the sectoral model, but the vast majority of UK government debt is financed domestically as shown above.

Government surpluses will take money away from the private sector thereby reducing the funds available to the private sector, damaging confidence thereby reducing the propensity to invest. Conversely the government expenditures that caused the deficit in the first place can have multiplier effects across the economy: in the above example the money spent on cars will enhance the balances of the various people that produce cars, they may buy some new cars themselves, spend more money in local shops etc. thereby increasing confidence and making investment decisions more likely.

Empirically there is limited evidence for the “crowding out” theory, look at the economic history described above and the experience of the last few years with rapidly rising deficits in the USA and UK economies and historically low interest rates.

And see this from the FT:

“In contrast to expectations, the paper finds that public sector R&D expenditure — whether directly or via subsidies — actually leads to an increase in private sector spending in R&D. A “crowding-in effect”, if you will.

By how much we hear you ask? Well, here’s a quote from the paper:

‘Our preferred elasticity for the OECD data set is 0.434 . . . suggesting that a 10% increase in government subsidies in a given year is expected to result in a 4% increase in private sector R&D the following year. This implies that $1 of additional public funds for R&D translates into $5 of extra R&D funded by the private sector at the mean values of public and private R&D’”

In addition, see this analysis from the Tax Foundation, most definitely not a left-wing organisation, in 2016:

“The foregoing sampling of recent econometric tests of the effect of real Federal deficits on real interest rates indicates that empirical studies of the issue are inconclusive.

Although theoretically sound research has at times identified the crowding out effect, the result is not persistent across time and across different methods of study. For example, in recent years, the study of crowding out has been virtually abandoned. One reason for this is that the effect simply hasn’t existed over the past seven years. If anything, in recent years, budget deficits are associated with low interest rates, not high ones. As the recession hit in 2009 and the budget deficit reached a historic high, interest rates plunged to new lows. This is the opposite of what a crowding out theory would predict.”

Paul Krugman noted this phenomenon in 2009. He explained, “a weak economy both drives up deficits and drives down the demand for funds, while a strong economy does the reverse.”He considered the association between borrowing and high interest rates a “falsity,” at least under the depressed economic conditions of the time. Under standard macroeconomic theory, government deficits when the economy is depressed can boost economic output and incomes. With higher incomes, the private sector may able to both afford to purchase the new government debt and still fund as much investment as it did before.

Even without a large output gap, though, with the improving economy of 2013 and 2014, the relationship has not really materialized. Low interest rates have become the norm. Even as overall economic conditions have picked up substantially, and even as projected deficits remained elevated, higher interest rates are nowhere in sight. The federal government has repeatedly predicted rising interest rates in its budget forecasts, but those rising interest rates have not materialized.

There are reasons to believe deficits raise interest rates under some circumstances. We may have seen this in the past, especially in earlier times when international capital flows may have been smaller. However, in recent times, we have not observed the connection…”

If you are a socialist, We need you now!✕

We are proudly biased towards Anti Capitalist, Anti Imperialist, Anti fascist! We believe we don’t need to mention you the importance of marxist magazine in this era! We are depending on our comrades only! Make an investment of $2.5/m in making a quality journal inclined to Marxism Leninism! Your one potential subscription helps us to maintain our global team! Subscribe and get access of all exclusive content available at the magazine section!