Introduction

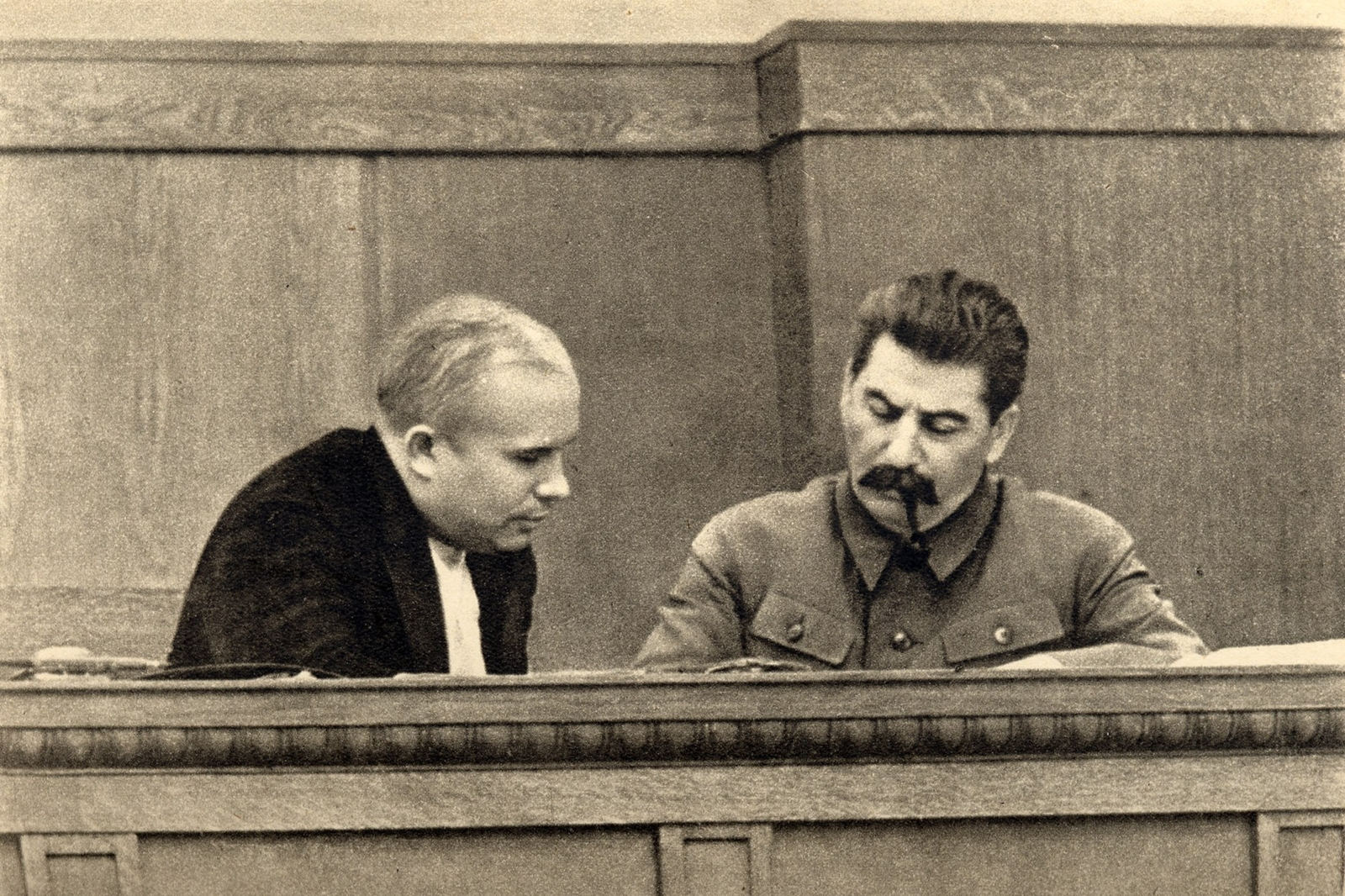

At a time of war in Europe and widespread concern that the conflict could spread, it is important to have a clear view of matters, yet more than ever we are subject to a mass of propaganda from the imperial powers. Readers will find the following essay by the military historian Luis Lázaro Tijerina invaluable in untangling the confusion and making sense of the current conflict in Ukraine and the deeper military background to it. As he shows, the nature of today’s Ukrainian army is best understood by looking back at the history of its development through the 20th century and through to the early 21st century, and this history has to be seen in the context of political developments and the political leadership to which the army is responsible.

I. The Stillbirth of the Ukrainian Army

Prior to February 24, 2022, there was no peace in Ukraine, but neither was there war. Rather, there was a ‘Phony War’ perpetrated by Western media voices, including specifically the US political elite’s voices, bragging with a certain bravado that they knew when the invasion of Ukraine by Russian forces would occur. As recorded by an American meteorologist: “The winter is cold in Eastern Europe, but the freezing temperatures are not slowing down Russia’s invasion into Ukraine. The forecast is for the temperature at night to reach below freezing in the 20s [Fahrenheit] over the interior parts of the country, with lows in the 30s within Kyiv. Areas around the Black Sea near Yalta on the south coast of the Crimean Peninsula will be a touch milder in the mid-30s. Russia has taken advantage of the cold and knows the freezing ground will provide a pathway for an attack”.[1]

A military theorist cannot, in the final analysis, wage war in the literal sense of the word, but can point the way through theoretical exposition: that is, by giving both concrete and factual observations about strategies and tactics that might lead to victory on the battlefield. In my view of military theory, it is instructive to admit that it is not simply from books that one can gain a theoretical idea on how to wage war, or even create an army. The actual commanders in the field do not have the time to read about the nature of strategy from a military manual, or from reading a book or an essay, whether from a famous military historian or an obscure theorist. The commander in the field is living in the moment and must make decisions in that moment that will be decisive in wearing down the enemy, even if it means a process of slow but methodical attrition in combat, and not the spectacular attacks that many military officers dream of, but which are rarely produced in an actual warfare.

In the case of the Ukrainian Army and its confrontation with the Russian Federation’s Armed Forces, it is important to look at its history, which is checkered at best and is filled, unfortunately, with political intrigues, fanatical ideological disruptions and a nationalism that is destructive to its military core. From Ukraine’s inception as a country, its armed forces were not a unified, cohesive force: instead of a unified military army, there were actually two main military forces that dominated the landscape. Ukraine is a land of endless partitions and re-definitions of national boundaries. For example, Galicia is a historical and geographical region in East-Central Europe, which in the modern era is divided between western Ukraine and eastern Poland, but this was not always the case. Ukrainian nationalists, the Russian Empire and Polish empire-seekers were in constant competition in the early period of the twentieth century, eventually leading to the first, modern Ukrainian armies. As noted by the Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine Army of the Ukrainian National Republic, what was known as the Ukrainian Galician Army (UHA) developed in the following way:

Ukrainian Galician Army (Українська галицька армія; Ukrainska halytska armiia [UHA]): The regular army of the Western Ukrainian National Republic (ZUNR), known as the Galician Army (Halytska armiia). It was formed around a nucleus consisting of the Legion of Ukrainian Sich Riflemen and other Ukrainian detachments of the Austro-Hungarian army, which recognized the authority of the Ukrainian National Rada and took part in the November Uprising in Lviv, 1918.[2]

It is obvious from the above that the components of this Ukrainian army’s nucleus did not form a cohesive nationalist force; it had been under the control of a leadership that was outside of Ukraine, being a part of the dying Austrian Hungarian empire.It was historically fated that the UHA would not hold up to the rigors of the competing spheres of other armies that it would have to face soon after World War I. According to the same source, the maximum strength of the Ukrainian Galician Army in 1919 numbered 70,000 to 75,000 men, including reserves. As the proportion of officers among its men was also very low, at only 2.4 percent, it was difficult to maintain a high degree of military professionalism. There was therefore a need to grant officer rank to non-Ukrainian specialists of the Austrian-Hungarian army, as well as to officers of the Army of the Ukrainian National Republic, which was also in existence at that time. To train young officers three infantry schools, an artillery school, and a communications cadet school were set up in Galicia, and one infantry and artillery school in central Ukraine. We see, again, that the UHA was spread out geographically and was not a Ukrainian army in the strictest sense of the word; this was likewise to be a serious problem for the Army of the Ukrainian National Republic. If, then, we study these two different armies, both of them claiming the allegiance of the Ukrainian people, we will be able to understand both the strengths and the weaknesses of the contemporary Ukrainian army in 2022, which keeps alive the myth of an invisible fighting force – but which is also capable of serious military capabilities when not encumbered by rabid nationalism and fascistic ideology; those have always been a problem within its ranks, particularly during World War II.

The demise of the UHA came about during the first years of the Russian Revolution, when the newly created Red Army was moving outside its Russian domain to further its revolutionary and national interests while at the same time fighting a civil war and confronting the Western Allies who had come to the aid of the White Russian forces in the naive hope of crushing the revolution. It was during this time that the Ukrainian-Polish War (1918–19) took place in the territory of Galicia, which as noted above is located in East-Central Europe and which to this day is still coveted by the competing nation-states that dwell in that region. The UHA enjoyed some initial military victories against the numerically stronger and better-equipped Polish forces, but these would not be enough to contain both the nationalist Polish armies and the Red Army that was now entering the fray. After the Chortkiv offensive, UHA forces retreated across the Zbruch river and joined up with the UNR Army to take part in the Ukrainian-Soviet War (1917–21), which was a war not necessarily fought with the best of intentions: both armies represented reactionary political bases that dreamed of empire and not of peace. Reduced by typhus to a mere 5,000 combat-ready men, the UHA finally found itself having to accept political and military absorption into the Red Army and it thus became the Red Ukrainian Galician Army. However, the General Staff of the Red Army demanded that the RUGA go into battle against the Polish forces. The RUGA’s First Brigade would be defeated and captured; its Second and Third brigades deserted the Red Army and allowed themselves to be disarmed by the Polish armed forces, and by the end of April 1920, the UHA had, for all intents and purposes, ceased to exist.

In my opinion, although I do not have access to archival materials regarding the formations of the early Ukrainian armies from 1917 to 1920 specifically, the Army of the Ukrainian National Republic closely resembles the present-day Ukrainian Ground Forces (Ukrainian: Сухопутні Війська ЗСУ Sukhoputni Viys’ka [ZSU]), also known as the Ukrainian Army. Like the Army of the Ukrainian National Republic in the early twentieth century, there is disunity among the masses of Ukrainian soldiers, as well as the officer staff concerning allegiance to the current Ukrainian regime whose bellicose behavior and inflammatory rhetoric against the Russian Government during the year 2022 have led to the so-called “Special Military Operations”, the invasion of Ukraine. However, before proceeding to a contextual observation of the modern Ukrainian Ground Forces, I would like to give a general overview of the birth and destruction of the Army of the Ukrainian National Republic.

The inception of the armed forces of Ukraine during the struggle for independence from 1917 to 1920, amid the tumult of the October Revolution in Russia, was a complex undertaking. The Army of the Ukrainian National Republic was never a regular army in the classical sense of the term, but rather a hodge-podge of various army factions that in fact belonged to armies outside of Ukraine’s borders, to states that were going through their own political crises, fueling chaos in those various armies as well. The history of the UNR Army can therefore be divided into three main phases: the periods of the Central Rada, the Hetman government, and the Directory of the Ukrainian National Republic. The formation of the various military units was part of the defeat in World War I of the Triple Alliance which included Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy, although Italy would eventually abandon that alliance. The irony was that it was Czarist Russia, a member of the Triple Entente with Britain and France, which sued for peace under the leadership of the Lenin, thus providing the Ukrainian nationalist leadership, though not necessarily all of the Ukrainian people, with the idea of an independent Ukrainian state that enjoyed self-determination.

The Russian army, in the long process of becoming the Red Army, saw the disbandment and breakdown of various army units, and with the revolutionary creation of Russia’s “Soviets of Soldiers’ Deputies”, the multinational Russian army began to create various military clubs and military assemblies along national lines. Ukrainian soldiers and officers, like other national minorities of the vast former Russian Army, found themselves creating a Ukrainian army distinct in character and values from the past Czarist Army. Especially with regard to this spontaneous, often even impulsive creation of the Ukrainian Army, I would like to quote from the Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine, in which the authors state the following:

Soviets of soldiers' deputies were elected by separate units. In units with a significant number of Ukrainian soldiers, separate Ukrainian soldiers' soviets were formed in parallel with the general soviets (in the rear they were called also soldiers' clubs, assemblies, and committees). Apart from the spontaneous national awakening, an important role in the formation of Ukrainian units was played by the Ukrainian Military Club (formed in Kyiv on 22 February on the initiative of Lt Mykola Mikhnovsky), which formed the Ukrainian Military Organizing Committee, whose task was to organize Ukrainian volunteer units. The appeals of the committee were very successful and stimulated the first manifestation of Ukrainian military strength during the All-Ukrainian military congresses in Kyiv (the first on 18–21 May 1917, the second on 18–23 June, the third on 2–12 November), which supported the Central Rada unconditionally, called for the separation of Ukrainian units from the Russian army and elected the first military leadership—the Ukrainian General Military Committee.

What should be mentioned is that Lt. Mykola Mikhnovsky, who would eventually commit suicide, was an idealist in the strict Ukrainian nationalist sense of the term. It was his utopian ideological vision of independent Ukrainian statehood without a pragmatic dialogue with the Russian Bolshevik Party that led to his ruin. Mikhnovsky was a dreamer, and his zeal for Ukrainian Statehood took on an almost religious flavor when he created the so-called “Ten Commandments” of the Ukrainian People’s Party, setting out his unrealistic vision of a Ukraine named in his honor and stretching between two mountain ranges, from the Carpathians to the Caucasus: a territorial quest which Russia would obviously never allow to become a reality.

Although there would be various mass movements by Ukrainian units along the Romanian front, the northern front, and the western front as the First World War ebbed towards its disastrous end and a new European power paradigm emerged, it was ironic how Ukrainian soldiers and officers began to actually find their freedom as a cohesive military force. As the sources quoted above admit: “the Russian commander in chief, Gen A. Brusilov, agreed to the official Ukrainianization of some units: the two-division 34th Russian Corps under the command of Gen Pavlo Skoropadsky (renamed the 1st Ukrainian) and the 6th Russian Corps (renamed the 2nd Sich Zaporozhian Corps) under the command of Gen Mandrake. Of 4 million Ukrainians in the Russian army in 1917, only 1.5 million were Ukrainianized, and the majority of these declared themselves neutral when it came to fighting the Bolsheviks or demobilized under the influence of Bolshevik agitation.”

From December 1918 to the fall of the Directory of the Ukrainian National Republic that was governed by various competitive leadership personalities, there would be no peace and no profound strategic war program. The warfare conducted by the UNR would find few or no allies while fighting two Russian armies, the Bolshevik or Red Army and the “White” Russian Army led by Anton Denikin. There was no single front from which the Ukrainian National Republic Army could fight and defeat its various adversaries, and the army itself was splayed out like a bleeding, lacerated hand. It even found itself faced with Polish forces who coveted parts of Ukraine, as they still do today (2022). Eventually, the UNR was forced to resort to the methods of guerrilla warfare. Although the war in Ukraine would continue to be fought against Russian and Polish military forces by guerrilla detachments under the Revolutionary staff, headed by Gen Yurii Tiutiunnyk, it was for all intents and purposes a dying army. In late 1921 the Revolutionary staff of the UNR ordered a ragtag partisan raid on the Right Bank (the so-called Second Winter Campaign) to be carried out by two groups—a Podilian unit and a Volhynian unit, made up of 1,500 volunteers from among the interned soldiers of the UNR Army. The Red Army destroyed each Ukrainian military unit. The Volhynian unit was surrounded and defeated near Bazar; 359 soldiers were executed (23 November 1921), and thus began the disbandment of the UNR and the first stage of the history of what would eventually become the Ukrainian Ground Forces in the modern era.

II. Nazified Ukrainian militias, the Ukrainian National Army, and Soviet Partisans

Every army throughout history, both ancient and modern, has at its core a political purpose. An army of a nation-state is none other than the instrument of the political ideology of that state. To put it bluntly, whatever the state apparatus dictates for its armed forces to achieve in a time of civil unrest within the state, or in waging war against an adversary or adversaries outside the boundaries of the nation-state, such orders are to be obeyed by the army leadership at all costs. The armed forces of a nation mirror the will of the political arm of the nation-state. In our time, that is in the early twenty-first century, the study of the Ukrainian Army, or Ukrainian Ground Forces, involves examining its political history, which is complicated, having initially been created by powers outside of Ukraine; there is also a dubious history in the form of extreme Ukrainian Nationalism and fascist aspirations, which to some extent have much in common with fascist armies of the past, but in this case resemble more closely the German Wehrmacht (German: “defense power”), the armed forces of the Third Reich. This is not to say that the modern Ukrainian Army is a completely fascist-infused military force, for that is not the case. In fact, the Ukrainian Ground Forces are made up of various political pockets that do not have a unified allegiance, except when they give effect to a statement about their military purposes or military actions in the field for propaganda purposes. Otherwise, the Army has disparate political wants that vary from the fascist extreme to a more moderate bourgeois political stance, and finally to a socialist, Marxist-Leninist approach to self-determination and independence for the Ukrainian nation-state.

These various political struggles are rarely noted by the Western media, which wants to keep up the myth of a unified Ukrainian Army fighting the invader, namely Russia and to some extent Belarus. This international myth of the Ukrainian troops and their officers fighting in the field against the so-called “barbaric” Russian soldiers will soon fade after a more sober and analytical observation of what the Ukrainian Ground Forces actually represent in terms of their military performance and their dedication to a just or unjust cause in terms of their response to Russia’s "special military operation" that began on February 24, 2022. What is important then is to continue to understand and analyze how the Ukrainian Army developed from World War I to the interwar years, then into the years of World War II, and its transformation first into a Soviet Ukrainian army and then finally into a full-fledged nationalist Ukrainian Army after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

I maintain that a unified national army cannot exist without a unified nation-state as its harbor, as its initial ground base of operations. Regarding the history of the Ukrainian army there was not initially a national identity. However, with the rise of a charismatic and fascist nationalist figure by the name of Stepan Bandera, such a cohesive zeal for statehood – along with an armed nationalistic militia – arose among the various peoples who referred themselves as “Ukrainians” even if they were of mixed heritage – Polish, Russian or Jewish. In an important work entitled Stepan Bandera: The Life and Afterlife of a Ukrainian Nationalist Fascism, Genocide, and Cult, from which I will quote extensively (as I view it as a profound history of Ukraine and of its military), the author, Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe, stated the dilemma of the Ukrainian people:

The changes to the map of Europe after the First World War served as a very convenient opportunity for the establishment of several new national states on the ruins of the Russian and Habsburg empires…

Like many other East-Central European nationalities, Ukrainians fought on both sides of the Eastern Front and, like some other peoples, established their own armies to struggle for a nation state. Yet in the case of Ukraine, they struggled rather for two different states than for one and the same.

In these observations by the German author, we see an initially fragmented nucleus: that is, there was not a unified Ukrainian Army fighting for an

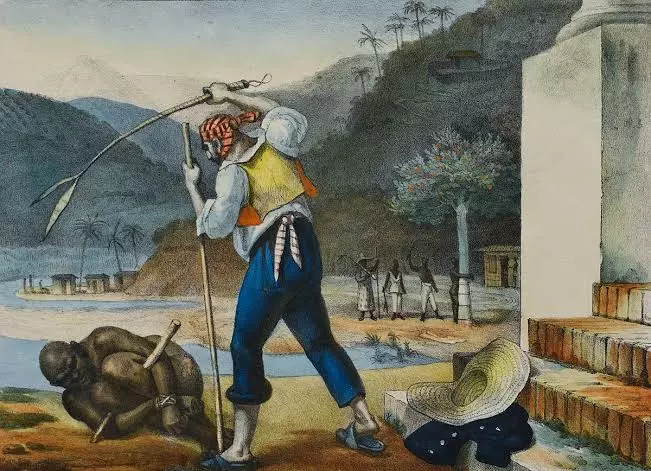

independent Ukrainian national state. It was during this revolutionary Ukrainian struggle that vicious pogroms were to ensue against Ukrainian Jews, in which it estimated that 1,182 pogroms occurred within Ukrainian boundaries and that 50,000 to 60,00 victims perished or were persecuted physically. It was only with the intervention of the Red Army that the pogroms would cease. This insidious nationalistic behavior and anti-Jewish violence would become a part of the ideological programs of the OUN-Z (Orhanizatsia Ukrains’kykh Natsionalistiv-za kordonom (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists-abroad) and OUN-B Orhanizatsia Ukrains’kykh Natsionalistiv-Bandera (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists-Bandera), which dominated the political theater of Ukrainian Nationalism throughout the Second World War before emerging in a more sophisticated and calculated way in the twenty-first century, so as to bring the European West and the United States into the internal political fray – although the CIA had also been involved with a reactionary Ukrainian insurgency against the Soviet Union during the Cold War period.

Even before Stepan Bandera emerged as the nominal leader of the OUN, the seeds of terroristic assaults upon perceived enemies were being promoted and instigated from abroad and within the Ukrainian homeland: “In May 1932, Bohdan Kordiuk became the new Providnyk of the homeland executive; Bandera became the deputy leader… The younger OUN members committed spectacular acts of terror and were encouraged to so by older members of the leadership in exile, who used the publicity for the purpose of collecting funds from Ukrainians living in North America. They advertised terror as a patriotic struggle against the occupiers.” As the reader will observe, the first seeds of the North American alliance with Ukrainian Nationalism had been sown and now the harvest is being witnessed: the whirlwind of political and military collusion with modern Ukrainian nationalism and its modern fascist ideology, part of the Bandera cult that was created before the Second World War. It is not just among the Western European nations, but among Americans, the majority being the dominant Anglo-American culture with its neo-liberal politics, that the stage has been set, so to speak, with a war on Russia. The oligarchs of Ukraine and the Ukrainian Ground Forces are tools within the paradigm of a proxy war.

It is important to give a description of Stepan Bandera, as he to this day has a great influence not only among thousands of far-right Ukrainians but also among Ukrainian military personal as well, and it was his fascist Ukrainian ideology which inspired to a large extent the Ukrainian Azov Movement that eventually embedded itself within the Ukrainian Armed Forces. Various US administrations have turned a completely blind eye to Azov’s military and political intentions, so enthralled and consumed are many American politicians. Furthermore, far-right American militias have attempted to copy the political ideals and military behavior of the Azov Regiment and the National Militia (Natsionalni Druzhyny) that came into existence in 2017. However, these Ukrainian fascist military organizations would have never been conceived without the background of the founding father of Ukrainian fascist military organization: Stepan Bandera. Bandera was born in 1909 to a Greek-Catholic priest married to the daughter of another Greek-Catholic priest [the Greek-Catholics are an Eastern rite church but are in full communion with Rome]. Bandera was born into the impoverished, socially backward Galicia (officially the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, created after the first partition of Poland). After the destruction of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after its defeat in World War I, Galicia briefly became the West Ukrainian People's Republic. After the Polish–Ukrainian War of 1918–1919, it was integrated into eastern Poland, and it was in this politically chaotic period that Bandera became radicalized. After becoming a student at the Lwów [Lviv] Polytechnic, he began to organize Ukrainian nationalist organizations. Bandera played a major role in orchestrating the 1934 assassination of Poland's Interior Minister Bronisław Pieracki and was sentenced to death. However, as fate would have it, the rising fascist Ukrainian leader’s sentence was then commuted to life imprisonment. In 1939, as a result of the German and Soviet invasions of Poland, he was freed from a Polish prison and moved to Kraków in the German-occupied zone of Poland. Eventually, Bandera would go to create the militia and help to develop the Insurgent Ukrainian Army that would ally itself with the armies of Nazi Germany.

It is important to understand that it is the United States, along with the NATO military pact that has replaced the Central Powers and Nazi Germany as the main force in dictating the political and military agenda or strategy in Ukraine, and it is my contention that Ukraine’s President, Volodymyr Oleksandrovych Zelensky (Ukrainian: Володимир Олександрович Зеленський), has a lot in common with Bandera, as both men, when studied critically, share a rabid, idealist nationalist disposition, except that where Bandera did not conceal his fascist political aspirations and agenda, Zelensky is more cunning in hiding his dream of creating a Ukrainian nation-state similar to Israel with its Zionist political hierarchy and hegemonic strategy for a greater Israel. Also, both men had artistic skills, as Bandera was known to be a fine singer, while we know that Zelensky was, and perhaps still is (in a political way now), an actor and comedian. I would argue that in his abilities to manipulate the leaderships of other nation states, Zelensky has done what Hitler could only dream of: he was able to seduce West European and American leaders. One does not have to be a general to lead an army into war, one need only know how to manipulate an uneducated population. The French writer, Gustave Le Bon, wrote in his classic work, The Crowd: A Study of The Popular Mind, wrote the following, which is relevant to the excessive, theatrical leadership of Bandera and Zelensky: “Given to exaggeration in its feelings, a crowd is only impressed by excessive sentiments. An orator wishing to move a crowd must make an abusive use of violent affirmations… It has been justly remarked that on stage a crowd demands from the hero of the piece a degree of courage, morality, and virtue that is never to be found in real life.” This part of Ukrainian history has affected the Ukrainian Armed Forces in the most subtle ways, so that the very thread of that history is lost on many Ukrainian troops and officers, though not all of them.

The vast majority of the racist pogroms which were planned and executed by the Banderites occurred in Eastern Galicia and Volhynia, but also in Bukovina. The deadliest of pogroms was perpetrated in the city of Lviv by the people's militia formed by OUN with direct participation of civilians, at the moment of the German arrival in Soviet-occupied eastern Poland. There were two Lviv pogroms, carried out in the span of just a month, each lasting several days: the first one from 30 June to 2 July 1941, and the second from 25 to 29 July 1941. The first took the lives of at least 4,000 Jews. It was followed by the killing of 2,500 to 3,000 Jews by the Einsatzgruppe and the "Petlura Days" massacre of more than 2,000 Polish Jews by the Ukrainian militants. It was during the pogrom of June 30, 1941 that Stepan Bandera declared a sovereign Ukrainian state in Lviv, and a few days later he was arrested by German occupation troops who opposed his nationalist, Ukrainian program, even though he was as much a fascist by ideology as the Nazi occupiers themselves. Bandera was eventually sent to be imprisoned in Nazi Germany. His nationalist and fascist supporters took over the command of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army two years later, in November 1943. Murder and genocide would be the order of the day for Ukrainian fascism during World War II, and it was Ukrainian nationalist militias and rural, backward Ukrainian peasantry as well as the Ukrainian Insurgent Army that would be culpable in the destruction of Ukraine’s national minorities, as well as of political adversaries such as members of the Ukrainian Communist Party.

The military collaboration of the OUN and the UPA, known as the Ukrains’ka Povstans’ka Armila (Ukrainian Insurgent Army), with the German Wehrmacht was profoundly brutal and historically significant in the annals of genocide in World War II. According to the German-Polish historian, Rossoliński-Liebe: “Between 1941 and 1944, almost all the Jews of Western Ukraine were annihilated by the Germans, with the help of the Ukrainian police and local people, and also by the OUN and UPA, both on their own and in collaboration with the Germans.” The Ukrainian Insurgent Army was fiercely engaged in guerrilla warfare against the Soviet Union, the Polish Underground State, and Communist Poland, as well as Nazi Germany. The Ukrainian fascist army was established by the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and arose out of different separate militant parts of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. These factions included the Bandera faction (the OUN-B), as well as some defectors from the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police, the mobilization of local urban Ukrainian populations, and others. The political leadership of the Ukrainian Insurgency army belonged to the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists—Bandera and thus was the prime perpetrator of the ethnic cleansing of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia.[3] During the war period from December 1941 to July 1943, the Ukrainian Revolutionary Army shared the same name (Ukrainian Insurgent Army, or UPA), and both armies aimed to

Although I have given only a short historical account of Ukraine’s fascist military forces, I would like the reader to bear with me regarding how this past history also dovetails into the modern Ukrainian Ground Forces with all their robust military acumen for waging war, even as they rely on outside forces to give them the arms necessary for waging total war against Russia. For despite the current situation that has developed from the history of the modern Ukrainian Army, we should not forget the Ukrainian partisans who fought against both the Wehrmacht and the Ukrainian fascist armies. To fail to recognize the struggle and hardships of Ukraine’s anti-fascist political forces is to fail to honor the progressive side of the history of the contemporary Ukrainian Army as well.

During the Russian Civil War, the Ukrainian Soviet Army was a field army of the Red Army, subject to the political leadership of Vladimir Lenin. This early Ukrainian socialist army was formed as a military armed force between November 30, 1918, and June 1, 1919. It was officially the Army of the second formation of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, under the commander-in-chief Vladimir Antonov-Ovseyenko. The Ukrainian Soviet Army is presumed to have had 188,000 soldiers in May 1919. The Ukrainian army was able to operate as a fighting force from January 4, 1919 on the territory of Ukraine as part of the Ukrainian Front.

The Army itself was finally disbanded on June 1, 1919, when eventually its troops came under command of Moscow. According to Ukrainian military archives: “The initial positive mood of the Ukrainian peasant soldiers had changed dramatically under the influence of the policy of War Communism. This had led to rebellions in parts of the Ukrainian Red Army at the end of April - early May 1919, of which the most serious was that of the 6th Ukrainian Soviet Division, called the Grigoriev Uprising”. Thus, it should be noted that there were cultural as well as political differences between the Ukrainian conscripts and their officers on how they viewed the Soviet Union in relation to Ukraine’s political independence.

It was during the early days of World War II that the Ukrainian Communist Party would initiate military action against the Nazi occupiers as well as eventually the Ukrainian fascist collaborators. It was also during this war period that the Ukrainian irregular forces or what were known as the Ukrainian partisan forces showed their mettle on the Ukrainian battlefields. The Ukrainian partisan movement during the last world war was of course complex, as Ukrainian territory had been subject to two occupying administrative forces, those of the Czechoslovak government and of the Hungarian regime in 1939. The historian of SOVIET PARTISANS IN WORLD WAR II described the beginning of the Ukrainian partisan movement thus:

… [The] Ukrainian population, which had been more or less passive under Czechoslovak administration, sharply opposed the harsher Hungarian rule. The largest native factions supported Ukrainian nationalism, but the Communist elements were much stronger in the Carpatho-Ukraine than in Galicia. Some Communist-led partisans groups were formed, although they were not very active until just before the Red Army in the early autumn of 1944… the Communist partisans evidently were permitted to act as though they were already on Soviet soil; they set up “national committees” which later served as nuclei for the Soviet transitional administration.

Regarding partisan warfare by Ukrainian Communist forces, it is also important to note the following anecdote on the detailed planning for a future conflict with a rising Ukrainian fascism as well as for a war with Nazi Germany. As explained by the source that I quoted above:

…regional Party officials apparently were unaware that higher Party authorities had drawn up plans for a clandestine organization to take over in the event of enemy occupation…. Evidently, prewar planning was confined to generalized schemes worked out by the central Party authorities. The lack of detailed preparation at the regional and local level may seem to indicate an incredible lack of foresight, but it more probably was inevitable corollary of the prevailing Soviet doctrine which envisaged a future war as an offensive campaign.

The British newspaper and online news site The Guardian published a fairly objective observation about the potential for modern partisan warfare in the Ukraine, stating:

The increase in partisan warfare, particularly in the country’s south around Kherson, follows warnings at the outset of Russia’s war against Ukraine that any area under occupation was likely to see the emergence of guerrilla warfare. The subject is one of the murkiest of the war in Ukraine. Both sides have an interest in exaggerating its prevalence: the Russians to justify crackdowns in areas they occupy and the Ukrainians to demoralise Russian troops. Also complicating the issue is assessing the extent to which attacks are being carried out by Ukrainian military sabotage groups or homegrown resistance groups. Partisans are usually defined as members of an armed group formed to fight secretly against an occupying force, for instance in Nazi-occupied Europe. The term holds more positive connotations than insurgent.[4]

What this British journalistic viewpoint omits or fails to take into consideration is that more than likely there will be Ukrainian civilians, including even Ukrainian military personnel, who will conduct partisan activity against the Zelensky regime, as they are as much opposed to seeing their nation come to utter ruin as are Russian citizens and Russian troops who are wedded to Ukraine by family ties and through ancestors who fought alongside the Ukrainian partisan resistance movement during World War II. Again, I emphasize that this Ukrainian partisan history is also a part of the modern Ukrainian Army’s history, which it cannot escape from, and its politically contradictory history is part and parcel of the way its troops view the war, the invasion or the “Special Military Operation”. Although as a military historian and theorist I would call the invasion a war, I would at the same time acknowledge that it is indeed a military operation against a specific political behavior by the Zelensky regime and by the United States and Great Britain which are supplying sophisticated arms to the Ukrainian Ground Forces in order to humiliate if not defeat the Russian military forces, which from the Russian perspective are waging a struggle against neo-Nazi forces and an oligarchical regime that is rife with political corruption and which has no deep interest in the welfare of ordinary Ukrainian people.