No social system that is not in harmony with nature can claim rationality and morality for itself. Therefore, the system that is most at odds with nature will also be overcome in terms of rationality and morality….The true struggle for democracy and socialism will only become a complete affair when it takes up the cause of women's freedom and nature's salvation. Only such a complete struggle for a new social system can lead to a meaningful way out of the current chaos.

Excerpt from Abdullah Öcalan's defense pamphlet "Bir Halkı Savunmak" (English: "Beyond State, Power and Violence”)

Nature is man’s inorganic body — that is to say, nature insofar as it is not the human body. Man lives from nature — i.e., nature is his body — and he must maintain a continuing dialogue with it is he is not to die. To say that man’s physical and mental life is linked to nature simply means that nature is linked to itself, for man is a part of nature.

Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts, 1844

If world GDP grows at the rate of 3% a year then it doubles after 24 years, after 35 years if the growth rate is 2%. Even if the energy mix is greener, do we really think that the planet can sustain that?

Stewart McGill, Socialism or Extinction

Introduction

The time has come to take the Degrowth movement seriously. In truth, this should have happened long ago. Firstly, let’s call it Décroissance, everything sounds a bit better in French.

Think of Décroissance as a planned reduction of energy and resource use designed to bring the economy back into balance with the living world in a way that reduces inequality and improves human well being. This definition is from Jason Hickel, of whom more later. Hickel also says that:

(Décroissance) is not just a critique of excess throughput in the global North; it is a critique of the mechanisms of colonial appropriation, enclosure and cheapening that underpin capitalist growth itself.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/social-sciences/degrowth#:~:text

According to a paper by Barbara Murraca in 2013:

…the idea of Décroissance - as it is widely employed by social movements - encompasses more than the critique of GDP as a measure for well-being. It embodies a radical questioning of the way social reproduction is intended and frames a multifaceted vision for a post-growth society.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/23460976

The term Décroissance emerged in France in the early 1970s. After the publication of the report by the Club of Rome, Limits to Growth, in 1972. The report itself was not in favour of zero or negative growth but it provoked politicians like Sicco Mansholt, and many others, to question the religion of growth and the values that led to the construction of that religion. Mansholt was a Dutch politician known for promoting an expansionist agricultural policy in Europe as commissioner for agriculture: he pushed hard for larger farms and increased subsidies so much that mountains of surplus butter were produced. He went through a radical change of outlook after he read an advance copy of the report in 1971. The conversion of someone like this made a lot of people listen.

http://www.ejolt.org/2014/03/growth-below-zero-in-memory-of-sicco-mansholt/

But they didn’t listen for long. Growth is a religion and religious belief takes a lot of shifting. Darwin was concerned that his theories of evolution would destroy religious belief: it’s still going strong, like it or not. It remains politically very powerful in the United States; Islam remains an important force across large parts of Africa and the middle east; Christianity is growing in China and there has been growing discontent in Japan with the growth of Islam in the country.

Maybe the survival of religion is down to the emptiness of life under capitalism (see Marx’s Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts, passim), maybe a symptom in itself of the religion of growth.

There is a big difference between these religious strands. The belief in something transcendental, offering something as an exemplar of perfection and a standard of against which our earthly behaviour should be judged, and an exhortation to act decently in the context of a shared humanity: this has been around for all of human history and its longevity would appear to express a basic human need. Even some avowed atheists show signs of religious devotion, e.g. vehement and sectarian followers of Richard Dawkins, and some Marxists who see his works as sacrosanct texts that form the source of all authority (More on this later).

The religion of growth is a relatively new creed, foisted upon us by the greedy priests of capitalism, actuated by a blind faith in the redemptive power of keeping the dispossessed working in order to maintain the wealthy in the style to which they have become accustomed. This imperative to growth, this belief that a social construction is an immutable natural law, this is what is driving the planet to destruction in the name of maintaining healthy returns on investment and shareholder value.

Castles Made of Sand, Fall into the Sea, Eventually…

Thanks to Jimi Hendrix for the title of this section, and for everything. I first thought about writing this article a couple of weeks ago when I heard on the BBC World service that the world is running out of sand.

I wrote at the time:

The Cambodians are dredging the Mekong River for the sand to fuel their construction boom, with hideous social and environmental consequences. We can’t go on like this, the capitalist imperative to grow is killing us, we need to grow out of it or die.

I did a bit of research and discovered that this has been an issue for a number of years, and one that emphasises the need to ditch the religion of growth and embrace that of redistribution and sustainability.

Sand is a critical ingredient of our lives. It is the primary raw material that modern cities are made from. The concrete used to construct shopping malls, offices, and apartment blocks, along with the asphalt we use to build roads connecting them, are largely just sand and gravel glued together. The glass in every window, windshield, and smart phone screen is made of melted-down sand. And even the silicon chips inside our phones and computers – along with virtually every other piece of electronic equipment in your home – are made from sand.

From this excellent article by Vince Beiser in 2019.

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20191108-why-the-world-is-running-out-of-sand

Vince is the author of The World in a Grain: The Story of Sand and How It Transformed Civilization.

He explains that creating the buildings and roads needed for the world's growing urban population requires vast volumes of sand. Sand has become the most-consumed natural resource on the planet besides water. People use some 50 billion tonnes of “aggregate” – the industry term for sand and gravel, which tend to be found together – every year. Enough to blanket the entire United Kingdom.

Desert sand is plentiful but can’t be used. The grains are the wrong shape. Eroded by wind, they are too smooth and rounded to lock together to form stable concrete.

The sand we need is the more angular stuff found in the beds, banks, and floodplains of rivers, as well as in lakes and on the seashore. Intense demand for that material is so intense that riverbeds and beaches are being stripped bare, farmlands and forests torn up to get at the precious grains.

“The issue of sand comes as a surprise to many, but it shouldn’t,” says Pascal Peduzzi, a researcher with the United Nations Environment Programme.

“We cannot extract 50 billion tonnes per year of any material without leading to massive impacts on the planet and thus on people’s lives.”

Herein lies the basic problem, we cannot inflict unlimited growth on a finite planet, and we cannot kid ourselves that the “green transition” will render it possible. We have to live differently: part of that transition, the all-important “revolution in your head,” comes from the recognition that we have enough for everyone to live well, redistribution rather than growth is that which matters, most economic growth ends up in the bank accounts of the already wealthy in the Global North anyway.

Rapid urbanisation and growth are the main driver of the sand crisis. Every year there are more and more people on the planet, with an increasing number of them moving from the countryside into cities, especially in the developing world. Across Asia, Africa, and Latin America, cities are expanding at a pace and on a scale far greater than any time in human history, driven by the imperative of economic expansion.

Urban populations have more than quadrupled since 1950 to around 4.2 billion, and the United Nations predicts another 2.5 billion will join them in the cities in the next three decades. The equivalent of adding eight cities the size of New York every single year.

Buildings homes for these people along with the roads to link them, requires prodigious quantities of sand.

As Beiser says:

In India, the amount of construction sand used annually has more than tripled since 2000, and is still rising fast. China alone has likely used more sand this decade than the United States did in the entire 20th Century. There is so much demand for certain types of construction sand that Dubai, which sits on the edge of an enormous desert, imports sand from Australia. That’s right: exporters in Australia are literally selling sand to Arabs.

But sand isn’t only used for buildings and infrastructure – increasingly, it is also used to manufacture the very land beneath their feet. From California to Hong Kong, ever-larger and more powerful dredging ships vacuum up millions of tonnes of sand from the sea floor each year, piling it up in coastal areas to create land where there was none before. Dubai’s palm-tree shaped islands are perhaps the most famous artificial land masses that have been built from scratch in recent years, but they have plenty of company.

Lagos, the largest city in Nigeria, is adding a 2,400-acre urban extension to its Atlantic shoreline. China, the fourth-largest nation on Earth in terms of naturally occurring land, has added hundreds of miles to its coast, and built entire islands to host luxury resorts.

That’s a lot of damage inflicted in order to create playgrounds for the global predator class.

River sand mining is also contributing to the slow-motion disappearance of Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, home to 20 million people, source of half of all the country’s food and much of the rice that feeds the rest of South East Asia.

Sea-level rise is one reason the delta is losing the equivalent of one and a half football fields of land every day. Another, is that people are robbing the delta of its sand. Back to Beiser:

For centuries, the delta has been replenished by sediment carried down from the mountains of Central Asia by the Mekong River. But in recent years, in each of the several countries along its course, miners have begun pulling huge quantities of sand from the riverbed. According to a 2013 study by three French researchers, some 50 million tonnes of sand were extracted in 2011 alone – enough to cover the city of Denver two inches deep…

In other words, while natural erosion of the delta continues, its natural replenishment does not. Researchers with the Greater Mekong Programme at the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) believe that at this rate, nearly half the delta will be wiped out by the end of this century.

To make matters worse, dredging the Mekong and other waterways in Cambodia and Laos is causing river banks to collapse, dragging down crop fields and even houses. Farmers in Myanmar say the same thing is happening along the Ayeyarwady River.

Sand extraction from rivers has also caused untold millions of dollars in damage to infrastructure around the world. The stirred-up sediment clogs water supply equipment. And removing all that material from river banks leaves the foundations of bridges exposed and unsupported. In Ghana, sand miners have dug up so much ground that they have dangerously exposed the foundations of hillside buildings, which are at risk of collapse. That’s not just a theoretical risk. Sand mining caused a bridge to collapse in Taiwan in 2000, and another the following year in Portugal just as a bus was passing over it, killing 70 people.

Awareness of the damage caused by our addiction to sand is growing. Some scientists are working on ways to replace sand in concrete with other materials, including fly ash, the material left over by coal-fired power stations; shredded plastic; and even crushed oil palm shells and rice husks. There are moves to develop concrete that requires less sand, while researchers are also looking at more effective ways to grind down and recycle concrete.

Time Slips Through Our Hands Like Grains of Sand, Never to Return Again.

(Robin S Sharma, The Monk Who Sold His Ferrari)

Development of alternatives to concrete will take time, and we are running out of that as quickly as the sand is slipping through our fingers. Just in the last week, this news came out:

Al Massira Dam, which sits around halfway between Casablanca and Marrakesh, contains just 3% of the average amount of water that was there nine years ago. Six consecutive years of drought and climate change, which causes record temperatures that lead to more evaporation, have threatened water supplies across the North African nation and hit agriculture and the economy in general.

And..

Climate change could move "into uncharted territory" if temperatures don't fall by the end of the year, a leading scientist has told the BBC.

Temperatures should temporarily come down after El Niño peters out in coming months, but some scientists are worried they might not.

"By the end of the summer, if we're still looking at record breaking temperatures in the North Atlantic or elsewhere, then we really have kind of moved into uncharted territory," Gavin Schmidt, the director of Nasa's Goddard Institute for Space Studies, told BBC News.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-68665166

The growth imperative is that which is killing us, we cannot go on producing at this rate without profoundly damaging the environment’s ability to sustain human life. The problem is accelerating, the top scientists in the field are surprised by how quickly temperatures are growing and the impact that growth is having on the planet already, we are so close to a tipping point that it makes no difference, we may have gone beyond that point already. So why do so many politicians talk incessantly about growth, why do more people on the left, the real left, not talk about the need to halt growth?

Like Losing My Religion…

“Losing my religion” is actually an old southern expression for being at the end of one’s rope, and the moment when politeness gives way to anger. This is the time to get angry and forget about being polite: we have to cast off the religion of growth and the values of capitalism that begat that creed.

Some on the left hold onto the faith as well. People look to, inter alia, Marx’s extolling the virtues of capitalist productionism in the Communist Manifesto, the Soviet Union’s drive to industrialise under Stalin that turned it into a modern society able to defeat Hitler, and China’s massive growth that has turned it into the workshop of the world (whilst questioning its status as a socialist nation, according to some).

With economic power comes military heft, and it’s easy to understand why both the Soviet Union and China took the path that they did. However, these are different times with different priorities, we can’t wish every developing nation to become like China: that would be an environmental catastrophe, and given China’s dominance across many manufacturing sectors, it would be very difficult anyway. (China’s huge manufacturing market share will be an important factor in any international effort to move the Global South from dependence on commodities and agriculture in a future world order based on redistribution, rather than growth.)

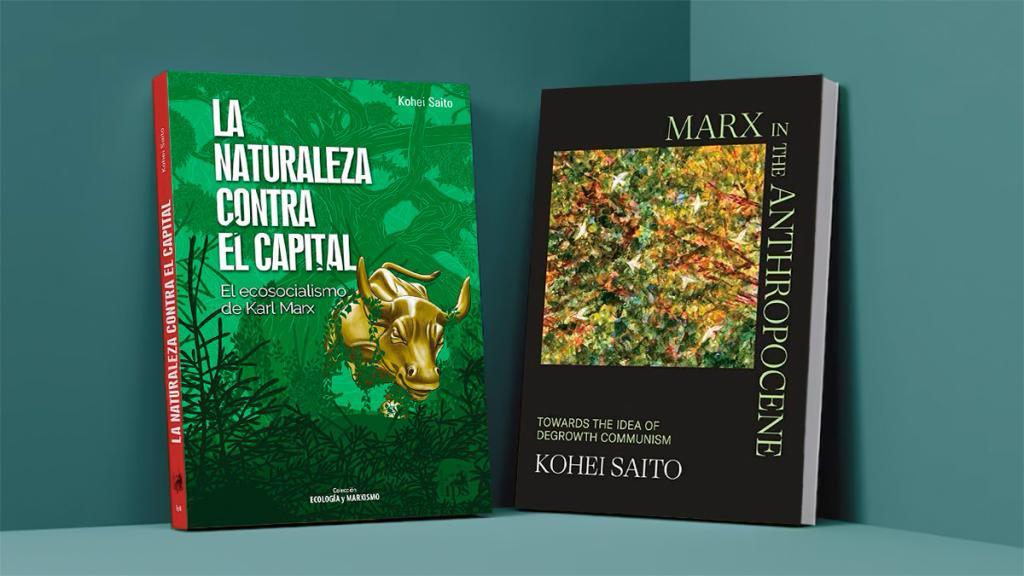

Kohei Saito’s Capital in the Anthropocene, a massive success that shifted 500,000 copies, and his subsequent Marx in the Anthropocene, have provoked interest amongst the left in the Décroissance agenda, and a lot of criticism for Saito. Some of the criticism was probably provoked by jealousy, not many Marxist academics sell that many. His repetition of the Décroissance line that people in the Global North enjoy an “imperial lifestyle” based on the exploitation of the Global South seems to have upset some people and provoked attacks on him as “anti-working class.”

Some of the phraseology may be problematic, and by no means everyone in Global North has the life of an emperor, but the basic contention is correct. For example, male life expectancy in Niger is 61; in France, the old colonial power that still has major economic interests in the country it’s 82. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the source of many of the minerals that produce our mobile phones and make the digital world possible, male life expectancy is 60; in the tech superpower of Finland, it’s 82.

Some of the neo-colonial factors behind this scandal are detailed in my Top Ten Economic Myths, an extract here:

Africa has large amounts of fertile land, but it struggles to make its agricultural sector profitable, leaving most African nations net importers of food. The continent imports roughly 80% of its food, spending more than $70 billion each year on staples, including maize, wheat, rice, soya and milk, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

The European Union (EU) is the biggest exporter of food to Africa, selling food products valuing nearly $20 billion to the continent each year according to European Commission statistics. Subsidies enable farmers in the political bloc to sell agricultural products at prices that don’t cover production costs. Most of these foods – wheat, milk powders, cereals, vegetable oils, poultry and vegetables – could be easily grown on African soil but unfair trade agreements give EU farmers an enormous advantage over their African colleagues, according to the FAO.

Free trade deals between the EU and some African, Caribbean and Pacific states known as the Economic Partnership Agreements (EPA) gives the EU cheap access to up to 83 percent of African markets. In exchange, the EU offers to eliminate certain tariffs and duties. Industry experts have repeatedly criticised the deals, saying they primarily benefit the EU because African companies are too weak to compete with European firms in a free trade environment. When Kenya, for example, refused to sign a deal in 2014 out of fear that subsidised agricultural products from the EU would ruin its food sector, the EU threatened to impose import tariffs on one of the country’s biggest foreign exchange earners, the cut flower sector. Kenya gave in and signed the agreement.

“African countries cannot compete” according to the UN economic analyst for East Africa, Andrew Mold. “As a result, free trade and EU imports endanger existing industries, and future industries do not even materialise because they are exposed to competition from the EU,” which affords little incentive to enter the market.

High EU import tariffs on processed foods force African farmers to export agricultural products raw, instead of adding value to them to increase profits. Raw foods that cannot be grown in Europe, such as coffee, are exempt from tariffs, while roasted beans have a 7.5 percent surcharge.

As a result, Africa, a key coffee grower, earned $2.4 billion from the sale of green coffee beans in 2014, while Germany earned $3.8 billion from coffee re-exports after roasting the beans according to Calestous Juma, Professor of International Development at Harvard University: “The concern is not that Germany benefits from processing coffee. It is that Africa is punished by EU tariff barriers for doing so.”

Historically and currently, much of our wealth in the North derives from exploitation of the South, Saito and the Décroissance people are right. This understanding has to form the basis for a socialist redistribution of wealth, income and power from the rich to the poor, not just within the Global North but from the North to the South. We have enough so that we can all live decently, the North has no inherent right to live so much better, and for so much longer than the South, it cannot be allowed to continue to exploit the South to further engorge itself with unnecessary, often conspicuous consumption that is destroying the planet. Ending all this might sound a little utopian, but given the rapid deterioration in our climate, we have to start thinking seriously about this if we want to survive.

There are legitimate criticisms of Saito. He spends a lot of time talking about various philosophical approaches in Marx in the Anthropocene that don’t really make a lot of difference to the basic argument and are alienatingly obscure:

First it is necessary to distinguish between the epistemological and ontological dimensions …Our knowledge is discursively mediated by scientific praxes and ‘making sense of nature’ is inevitably constrained by social power relations. As long as human access to nature is conditioned by language, there is no full transparent and direct access to external nature as such. This does not mean, however, that external nature independent of humans does not exist as if nature itself were ontologically constructed.

Just the stuff to give to the workers, that will get them on the Décroissance side.

Saito also spend much of the book trying to claim Marx as a Décroissance warrior. He talks a lot about Marx’s work on the metabolic rift, quotes such as that above from the EPM and discusses whether Marx abandoned Historical Materialism in later life, with reference to much of the work discussed in Kevin Anderson’s brilliant Marx at the Margins. It’s all interesting but it doesn’t really make any difference to us right now, and I speak as a huge fan of Marx. The Décroissance case stands strongly by itself, it does not need to be justified with reference to “what Marx really meant,” the works of Marx do not form a scriptural authority that cannot be questioned, and they are not the only sources of truth. This is another case where we need to lose the religious tendency and focus on concrete solutions for concrete problems, in the case of sand, semi-literally. Marx would have understood this approach.

Jason Hickel.

Without denying the towering genius of Marx, Hickel is a more contemporary writer and a better “nuts and bolts” guide to the need for Décroissance.

In Less is More and The Divide, Hickel makes a very cogent case for the Décroissance agenda and for the need to replace the capitalism that perpetuates environmental destruction and criminal levels of inequality and exploitation.

He points out that half of Asia’s population depends on water from Himalayan glaciers, for agriculture as well as drinking water. For thousands of years, the run-off from these glaciers has been replenished each year by new ice, but now the ice is melting faster than it is being replaced. If we hit 3 or 4 degrees centigrade warming over pre-industrial levels, and we are on track, most of those glaciers will be gone by the end of the century. He then says:

It’s high income countries that are the problem here, where growth has become completely unhinged from any concept of need, and has long been in excess of what is required for human flourishing. Global ecological breakdown is being driven almost entirely by excess growth in high-income countries, and in particular by excess accumulation among the very rich, while the consequences hurt the global south and the poor disproportionately. Ultimately, this is a crisis of inequality as much as anything else.

https://www.jasonhickel.org/less-is-more]

He’s right, but China and India should not be exonerated. Yes, their per-capita emissions are lower than those of the global north; yes, much of their production is driven by meeting the demand of the North. However, they both plan to use more coal and have an addiction to growth as a means of increasing their status and military capabilities as well as raising living standards, understandably given American aggression and determination to hold onto its status as Number One Superpower. This is where international cooperation is a necessity if we are to escape from the current path towards destruction.

As I wrote in Socialism or Extinction:

There is an irony here in that China’s domination of the solar panel market is partly due to low wage costs in a labour-intensive industry and to the cheap coal used to produce the panels. Concerns are mounting in the U.S. and Europe that the solar industry's reliance on Chinese coal will create a big increase in emissions in the coming years as manufacturers rapidly scale up production of solar panels to meet demand. That would make the solar industry one of the world’s most prolific polluters, analysts say, undermining some of the emissions reductions achieved from widespread adoption. This is an important industry for China and it is understandably reluctant to give up a competitive advantage by moving to more environmentally friendly but dearer fuel; the big western companies are driven by profit and will seek the cheapest product they are little concerned with the irony of a product being sold on its ecological benefits being such a large contributor to emissions.

China has pushed down the price of panels so sharply that solar power is now less expensive than electricity generated from fossil fuels in many markets around the world. Imports of the solar cells that make up the panels are also flooding into the U.S. and Europe, shipments either coming directly from China or contain key components made in China.

“If China didn’t have access to coal, then solar power wouldn’t be cheap now,” said Robbie Andrew, a senior researcher at the Centre for International Climate Research in Oslo. “Is it OK that we’ve had this huge bulge of carbon emissions from China because it allowed them to develop all these technologies really cheaply? We might not know that for another 30 to 40 years.”

And do we have those 30–40 years? Recent analysis referred to above would suggest that is questionable. The transition to solar is important, should be prioritised and the West should be prepared to pay a price for that transition that does not lead to increased emissions down the supply chain, the diktats of capitalism cannot be allowed to undermine our future.

Some form of cooperation with China such as an agreement to continue buying at a higher price for a number of years during their transition to more sustainable energy sources is a possibility, the diktats of the new Cold War can also not be allowed to undermine our future. This would defend jobs in China and would dissuade them from subsidising coal even further in order to keep competitive.

See this link for Socialism or Extinction

Hickel sums the basic issues up nicely in Less is More:

More growth means more energy demand, and more energy demand makes it all the more difficult - impossible in fact - to roll out enough renewables to cover it in the short time we have left.

Even if this wasn’t a problem, we must ask ourselves: once we have 100% clean energy, what are we going to do with it? Unless we change how our economy works, we’ll keep doing exactly what we are doing with fossil fuels: we’ll use it to power continued extraction and production at an ever-increasing rate, placing ever-increasing pressure on the living world, because that’s what capitalism requires. Clean energy might help deal with emissions, but it does nothing to reverse de-forestation, overfishing, soils depletion and mass extinction. A growth-obsessed economy powered by clean energy will still tip us into mass extinction.

Debt-fuelled capitalism depends on growth. If the economy does not grow, debts pile up that cannot be repaid, fixed capital assets do not produce enough to pay for their upkeep nor the debt that was incurred to purchase them, debt that was often incurred and structured on the bases of growth in income and production.

Green Transition Illusions

There are also two crucial things to remember about “green” energy. Firstly, under capitalism, its adoption will only be widespread if it increases profitability, and this is not just a matter of making it cheaper through subsidy etcetera. In The Price is Wrong, Why Capitalism Won’t Save the Planet, Brett Christophers shows how both the structure and the profit imperatives of the global electricity industry militates against the uptake of wind and solar energy, even if those cleaner sources of energy are cheaper. It’s the profitability that matters. This is aggravated by the fact that the uncertainties regarding profitability makes banks less likely to finance renewable energy projects.

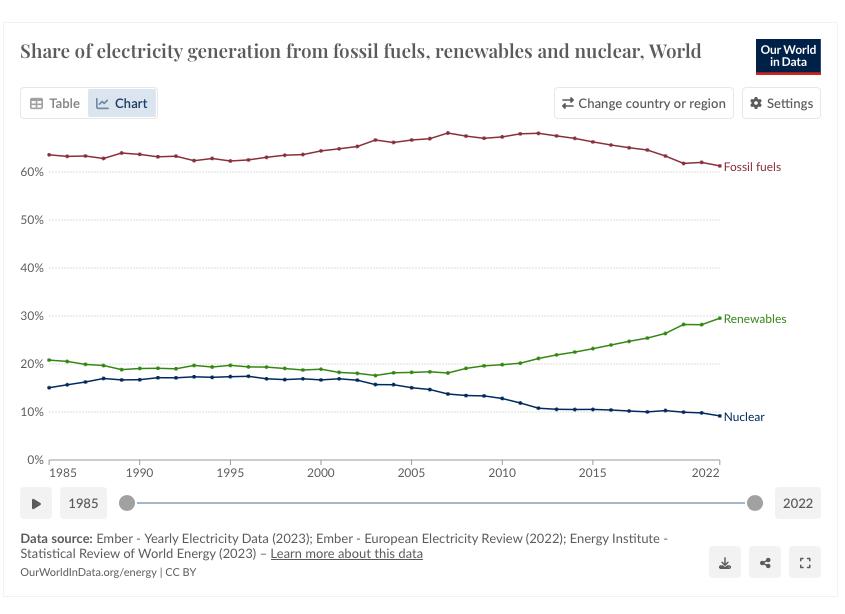

This is crucial: electricification is a fundamental part of the move to clean energy, if it continues to be provided through fossil fuels, we have a huge problem. For all the talk, Christopher shows that the share of global electricity produced by fossil fuels is pretty much the same today as it was in 1985. No capitalist way out of this.

https://www.versobooks.com/en-gb/products/3069-the-price-is-wrong

Secondly, green energy still inflicts a wound.

Approximately 2.2 million litres of water are needed to produce one ton of lithium.

A recent Friends of the Earth Report claims:

The production of lithium through evaporation ponds uses a lot of water - around 21 million litres per day. Approximately 2.2 million litres of water are needed to produce one ton of lithium. The extraction of lithium has caused water-related conflicts with different communities, such as the community of Toconao in the north of Chile.

Pollution from tyre wear can be 1,000 times worse than that which comes out of a car’s exhaust, Emissions Analytics has found. The Increased popularity of SUVs, larger and heavier than standard vehicles, exacerbates this problem – as does growing sales of heavy Electric Vehicles (EVs) and widespread use of budget tyres.

Fitting only high-quality tyres and lowering vehicle weight are routes to reducing these non-exhaust emissions.

It’s not enough to move to EVs: they are heavier, which causes more tyre-emitted pollution, and their manufacture damages the environment, though mostly in places that the Global North doesn’t care about it, they exist only to further the growth imperative.

The mining of silver and other metals important to the green transition is also damaging to the environment, we have to change the way we live, and think.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0048969723005417

Conclusion

I end with an extract from Socialism or Extinction:

The driving force of capitalism, it’s innate and unquestioned imperative, is growth. Growth of revenue, growth of profits, growth of markets, growth of market share. People who work in capitalist enterprises, from CEOs to junior salesmen are given growth related targets, people who advance in advance to senior positions in these organisations do so because they have grown income, profits, market share etc….

To effect real change and the transformation necessary to save the planet we need to challenge the vested interests of corporate power and the political authority with which it is intimately connected, the above analysis provides plenty of examples. We need to reset the purpose of economic activity and challenge the growth imperative. Sustainability policies need to be coupled with redistribution of income and wealth, nationally and between nations with particular focus on justice for the developing world and emphasis on collaboration rather than political/economic competition.

The attitudes and culture perpetuated by capitalism such as the heedless consumerism that drives the fashion industry, the greed that places 10% of world GDP into tax havens, the indifference to the deaths of the workers in Rana Plaza that made our cheap t-shirts in hideous conditions, the willingness to accept more pollution as long as it shaves 10 minutes of your car journey; these must also be fought in the interests of building a new society in which the welfare of the collective becomes a priority, without completely obliterating the individual and their rights.

The working of the mythical “free market” cannot be allowed to lead the fight for survival no more than can the blinkered greed that dictates its priorities and rationalisations. We need coherent, integrated plans to escape this crisis that recognise the comprehensive transformation required.

We need the collective harnessing of resources in a coherent manner aimed at achieving outcomes that enable us to survive, maximise the common good and pursue the priorities of protecting the most vulnerable and elevating the most oppressed; in short, socialism or extinction.

Editor's Note:

The views and informations expressed in the article are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect the views of The International. We believe in providing a platform for a range of viewpoints from the left.

"The International" belongs to you.✕

Please take a moment to read this. We apologize for any interruption, we want you to know "The International" seeks your valued support at this time. We've proudly served as a pioneering online platform, delivering ad-free media content. With only 2% of our readers opting for a subscription, any contribution you choose holds immense significance—whether it's an annual fee of $25 or a monthly payment of $2.5. — The "The International" Team, committed to providing you with enlightening perspectives. We want to highlight that this sum is even less than what you'd spend on a cup of coffee, yet it greatly aids in sustaining our efforts to perpetuate and enhance your esteemed initiative.